Luther (Fall of Babylon)

This story captures the incredible drama and tension of one of history’s most pivotal moments. The Diet of Worms was essentially a theological trial that became a political earthquake, with Luther’s defiance marking the point of no return for the Protestant Reformation.

The Summons

“Here I Stand… Or Do I?”

The parchment crackled like kindling in Martin Luther’s trembling hands, its imperial seal catching the pale March light that filtered through his study window. He read the words again, though they had already burned themselves into his memory with the permanence of a brand:

“We command you to appear before us and the estates of the Holy Roman Empire in the city of Worms, there to answer concerning your books and your doctrine…”

Twenty-one days. He had twenty-one days to travel to what might well be his execution.

“Martin?” The voice belonged to Georg Spalatin, Frederick’s secretary, who had delivered the summons and now watched his friend’s face with growing concern. “You’ve gone white as parchment.”

Luther set the document on his desk with deliberate care, as if it were made of glass. Outside, the sounds of Wittenberg’s morning market drifted through the window — vendors hawking their wares, children laughing, the ordinary rhythms of a world that seemed suddenly distant and unreal.

“They mean to burn me,” Luther said quietly. “The safe conduct is meaningless. They burned Jan Hus despite his imperial protection.”

Spalatin stepped closer, his diplomatic training warring with genuine affection for the monk who had become the most dangerous man in Europe. “The Elector believes — “

“The Elector believes what he must to sleep at night,” Luther interrupted, his voice sharpening. “But we both know what happens to heretics who trust imperial promises.”

The door burst open without ceremony, and Philip Melanchthon rushed in, his young face flushed with exertion and fear. Behind him came Johannes Bugenhagen, Lucas Cranach, and several other members of Luther’s inner circle. Word had spread with the speed that only catastrophic news could achieve.

“Is it true?” Melanchthon demanded, his eyes darting to the document on Luther’s desk. “They’ve actually summoned you?”

Luther nodded, feeling the weight of their stares like physical pressure. These men had followed him into theological revolution, had seen their comfortable academic world turned upside down by his defiance of Rome. Now they faced the possibility of watching their leader march willingly to his death.

“You cannot go,” Bugenhagen declared, his normally measured tone cracking with emotion. “It’s suicide, Martin. Pure suicide.”

“And if I don’t go?” Luther asked, though he already knew the answer. “If I flee like a coward? What becomes of everything we’ve worked for? What becomes of those who’ve dared to believe that salvation comes through faith alone, not through the corrupt machinations of priests?”

The room fell silent. Outside, a bell began to toll the hour, each chime echoing like a countdown.

Cranach, the court painter whose brush had captured Luther’s likeness for distribution across Germany, spoke with the practical wisdom of an artist who understood image and symbol. “If you go and they kill you, you become a martyr. If you flee, you become a coward. But if you stay silent, you remain alive to continue the work.”

“Do I?” Luther’s laugh was bitter. “Do I remain alive, or do I become something worse than dead? A living man whose silence gives consent to every abuse, every corruption, every soul sold for papal gold?”

He moved to the window, pressing his palm against the cold glass. In the square below, a group of students had gathered around a traveling preacher — one of the many who had taken up Luther’s message and carried it to the common people. The irony was not lost on him that his own words, scattered like seeds on the wind, had created this moment of impossible choice.

“I keep thinking of Abraham,” Luther said, his breath fogging the glass. “Called to sacrifice his son, not knowing that God would provide a ram in the thicket. But what if there is no ram this time? What if God requires the full sacrifice?”

Melanchthon approached, his scholarly mind grappling with the theological implications. “But Abraham’s faith was tested, not punished. Perhaps… perhaps this is your test. Perhaps God will provide.”

“Or perhaps,” Luther turned from the window, his face etched with a pain that went beyond physical fear, “perhaps I have been wrong about everything. Perhaps I am the heretic they claim, leading souls to damnation through my pride and stubbornness.”

The words hung in the air like an accusation. For three years, since his ninety-five theses had shattered the comfortable assumptions of Christendom, Luther had wrestled with this fundamental doubt. What if his rebellion against papal authority was not divinely inspired reform but satanic rebellion? What if every soul that followed him away from Rome was damned by his influence?

Spalatin, ever the diplomat, tried to redirect the conversation toward practical matters. “The Elector has arranged for an armed escort. You’ll travel in comfort and safety until you reach Worms. After that…” He shrugged helplessly.

“After that, I’m in the hands of men who have already decided my fate,” Luther finished. “Tell me, Georg, what does Frederick truly think? Not what he tells you to tell me, but what he whispers to his advisors when he thinks no one is listening?”

The question caught Spalatin off guard. His loyalty to his employer warred with his friendship with Luther, and the internal struggle played across his features. Finally, he sighed. “He fears you’ve overreached. He believes in your cause, but he’s terrified that your death will destroy any chance of real reform. He would prefer you to… moderate your position.”

“Moderate my position.” Luther repeated the words as if tasting something bitter. “Tell me, if a man sees his neighbor’s house on fire, does he moderate his warning? Does he politely suggest that perhaps the flames might be worth investigating at some convenient future time?”

He began to pace, his black robes rustling with each agitated step. “The Church sells salvation like meat in the marketplace. Bishops live in palaces while the poor starve outside their gates. The Pope himself wallows in luxury that would make Caesar blush. And I should moderate my position?”

“But if you die, nothing changes,” Bugenhagen pleaded. “If you live, even in exile, you can continue to write, to teach, to reform. Dead martyrs inspire songs, Martin. Living reformers change the world.”

Luther stopped pacing and fixed his friend with a stare that seemed to see through flesh to soul. “And what of my soul, Johannes? What of the account I must give to God for every truth I failed to speak, every corruption I allowed to continue through my silence? Do you think the Almighty will accept ‘I was being practical’ as an excuse for abandoning His truth?”

The debate raged for hours, circling like water around a drain. Arguments were made and countered, scriptures quoted and reinterpreted, fears voiced and dismissed. As the shadows lengthened across the floor, Luther found himself remembering another conversation, another crossroads that had brought him to this moment.

It had been in this very room, three years ago, that he had written his letter to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz, challenging the sale of indulgences. He had been a different man then — still believing that Rome could be reformed from within, still trusting that reasonable men would listen to reasonable arguments. How naive he had been. How utterly, completely naive.

The Church’s response had been swift and brutal. Condemnation, excommunication, the burning of his books in public squares. They had made him into the very thing he had never intended to become: a revolutionary. And now they demanded that he appear before them like a lamb before slaughter.

As evening approached, his friends began to drift away, each leaving with promises to pray for his decision. Melanchthon lingered longest, his young face creased with worry.

“Whatever you decide,” he said quietly, “know that you have changed everything. The questions you’ve raised cannot be unasked. The truths you’ve revealed cannot be hidden again.”

When Luther was finally alone, he knelt before the wooden crucifix that dominated his study. The carved figure seemed to stare down at him with eyes that held both accusation and invitation. Christ had faced His own summons, had walked His own road to judgment. But Christ had known His mission with divine certainty. Luther felt only the terrible weight of human doubt.

“Show me,” he whispered to the carved figure. “Show me what You would have me do.”

The night passed in sleepless agony. Luther prayed, paced, read scripture, and wrestled with his conscience like Jacob wrestling with the angel. By dawn, he had reached a decision that felt less like choice than like surrender to an inevitable tide.

He found Spalatin waiting in the chapel, apparently having spent the night in similar vigil. The secretary’s face was drawn with exhaustion and worry.

“I will go,” Luther said simply.

Spalatin’s shoulders sagged with what might have been relief or despair. “The Elector will be pleased. When do you wish to depart?”

“Today. This morning. If I wait longer, I may lose my nerve entirely.”

The next hours passed in a blur of preparation. Word of Luther’s decision spread through Wittenberg like wildfire, drawing crowds to the streets. Students wept openly. Townspeople pressed forward to touch his hand, to receive some blessing from the man who had dared to challenge an empire.

As Luther climbed into the wagon that would carry him toward his fate, he looked back at the city that had been his home, his refuge, his center of operations for the revolution he had never intended to start. The university towers gleamed in the morning sun, and for a moment he could almost pretend this was simply another academic journey.

But the imperial herald riding ahead of his wagon, the armed escort, and the crowds that were already gathering to follow his procession gave lie to any such comfortable illusion. This was not a journey to academic debate. This was a funeral procession — the only question was whether it would be his funeral or that of the old order he had challenged.

As the wagon rolled through the city gates, Luther opened his breviary and began to read the Psalms. “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want…” The familiar words provided some comfort, though they could not quiet the voice in his head that whispered he was riding toward his own destruction.

Behind him, Wittenberg receded into the distance. Ahead lay Worms, and an encounter that would determine the fate of souls he had never met, in a world he was helping to create but might not live to see.

The road stretched ahead like a question mark, and Martin Luther, monk and revolutionary, rode toward whatever answer awaited him.

The Trap Springs

“Books, Fire, and Souls”

The great hall of the Bishop’s Palace in Worms had never contained such concentrated power in its stone walls. Banners bearing the arms of every major German principality hung from the vaulted ceiling, their silk and gold thread catching the light from hundreds of candles. At the far end, on a throne that seemed to dwarf even its occupant, sat Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Spain, ruler of more territory than any man since Charlemagne.

He was younger than Luther had expected — barely twenty-one, with the soft features of pampered youth. But his eyes held the calculating coldness of a man born to command empires. Those eyes now fixed on the small door through which Luther would enter, and Charles felt the weight of history pressing down on his shoulders like a physical burden.

“Your Majesty,” Cardinal Aleander whispered from his position beside the throne, “remember that this man has already been declared a heretic by His Holiness. This proceeding is merely a formality — a chance for him to recant publicly before his inevitable punishment.”

Charles nodded absently, his attention focused on the assembled crowd. Every seat was filled, every standing place occupied. Princes and bishops, knights and merchants, scholars and diplomats — all of Germany’s elite had come to witness this confrontation. The air thrummed with barely contained tension, like the moment before a thunderstorm breaks.

In the third row, Frederick the Wise sat with carefully composed features, though his hands gripped the arms of his chair with white-knuckled intensity. His secretary Spalatin stood behind him, pale and nervous, repeatedly checking the timepiece that hung from his belt. Everything they had worked for, every careful political calculation, came down to the next hour.

Johann Eck paced near the table where Luther’s writings had been arranged in towering stacks — thirty volumes of theology, controversy, and what many in this room considered heresy. As papal representative and Luther’s longtime adversary, Eck had orchestrated this moment with the precision of a master chess player. The trap was set, the pieces in place. All that remained was to spring it.

The massive oak doors swung open with a groan that echoed through the sudden silence. Every head turned, every breath held, as Martin Luther stepped into the hall.

He was smaller than many had expected, this man who had shaken the foundations of Christendom. His black Augustinian robes made him appear almost ghostly against the rich tapestries and gleaming armor of the assembled nobility. But there was something in his bearing — a coiled tension, a sense of barely contained force — that commanded attention despite his modest stature.

Luther’s eyes swept the assembly, taking in the overwhelming display of power arrayed against him. For a moment that seemed to stretch into eternity, he stood frozen in the doorway. The weight of hundreds of stares pressed against him like a physical force. These were the men who ruled the German lands, who commanded armies and controlled the fate of millions. And they were all here to witness his destruction.

This is madness, he thought. What am I, one simple monk, against all this?

But then his gaze found the stacks of books on the table, and something hardened in his chest. Those volumes represented years of study, prayer, and careful reasoning. They contained truths that had cost him everything — his security, his position, his peace of mind. They were more than books; they were the crystallized essence of his struggle to understand God’s will in a corrupt world.

He walked forward with measured steps, his sandals clicking against the stone floor in the profound silence. Every eye followed his progress, and he could feel the collective held breath of the assembly like a living thing pressing against his consciousness.

Emperor Charles leaned forward slightly, studying this man who had caused such upheaval in his domains. Luther was clearly terrified — his face was pale as parchment, and sweat beaded on his forehead despite the cool air. But there was something else in his bearing, something that reminded Charles uncomfortably of his own grandfather Ferdinand, who had never backed down from a fight no matter the odds.

When Luther reached the designated spot before the throne, he performed a bow that was correct but notably brief. Not the deep, prolonged genuflection that papal protocol demanded, but the minimal courtesy due to temporal authority. The message was subtle but unmistakable — he acknowledged Charles as emperor, but not as his spiritual superior.

Eck stepped forward, his voice carrying clearly through the hall with the practiced authority of years in ecclesiastical courts. “Martin Luther, you have been called before His Imperial Majesty and the estates of the Holy Roman Empire to answer concerning your books and your doctrine.”

He gestured toward the table with theatrical flourish. “Do you acknowledge these books, displayed here, as your own work?”

Luther turned to examine the volumes, though he knew their contents by heart. There was his commentary on Galatians, his treatise on Christian liberty, his attacks on papal authority, and dozens of other works that had spread his reforming message across Europe. Seeing them assembled like evidence in a criminal trial sent a chill through his bones.

“The books are mine,” he said, his voice carrying despite its quiet tone. “I acknowledge them.”

A rustle of movement swept through the assembly. The first hurdle had been cleared — Luther had not attempted to deny authorship of his controversial writings.

Eck smiled with the satisfaction of a hunter who had just seen his prey step into a snare. “Do you defend all these books and their contents, or are you prepared to retract any part of them?”

The question hung in the air like an executioner’s axe. This was the moment everything had been building toward. A simple “yes” would condemn Luther as an unrepentant heretic. A “no” would destroy his credibility and abandon thousands of followers who had trusted his teachings.

Luther opened his mouth to speak, then closed it again. The silence stretched, becoming uncomfortable, then excruciating. Somewhere in the back of the hall, someone coughed, the sound explosive in the profound quiet.

The emperor’s eyes narrowed. Was the heretic about to collapse? Would this great confrontation end not with defiant martyrdom but with whimpering capitulation?

Luther’s mind raced through possibilities, each more terrifying than the last. The easy path lay before him — recant, apologize, submit to papal authority, and perhaps live to see another sunrise. But what of Philip Melanchthon, waiting anxiously in Wittenberg? What of the thousands of ordinary Christians who had found hope in his message that salvation came through faith alone, not through the corrupt machinery of indulgences and papal politics?

God help me, he prayed silently. Show me what You would have me do.

And in that moment of supreme crisis, something unexpected happened. Luther felt his panic beginning to ebb, replaced by a growing sense of clarity. These men could kill his body, but they could not touch the truth he had discovered in Scripture. They could burn his books, but they could not unwrite the words that had already spread across Europe like wildfire.

“This touches God and His Word,” Luther said finally, his voice gaining strength with each word. “This touches salvation — the greatest thing in heaven and earth. I would be rash to answer without due consideration, lest I say too little or too much and fail in my duty to God and man.”

The response sent shockwaves through the assembly. No one had expected the heretic to ask for time to consider. It was unprecedented, almost insulting to the dignity of the imperial court.

Eck’s face flushed with anger. This was not how the script was supposed to unfold. Luther was supposed to either recant immediately or defy them immediately, providing clear justification for his condemnation. This request for delay was throwing the entire proceeding into chaos.

“You have had years to consider these matters,” Eck snapped. “Your books have been published and distributed. Surely you know your own mind regarding their contents?”

Emperor Charles raised a hand for silence, his youthful face thoughtful. The political implications of Luther’s request were complex. Granting time might be seen as weakness, but refusing it might make Charles appear tyrannical. And there were those among the German princes who were already grumbling about papal interference in imperial affairs. Become a member

“How much time do you require?” Charles asked, his voice carrying the crisp authority of absolute power.

“One day, Your Majesty. Until tomorrow at this same hour.”

The emperor conferred briefly with his advisors in rapid Spanish, their whispered conversation inaudible to the rest of the assembly. Finally, he nodded.

“It is granted. You will return tomorrow at six o’clock to give your final answer.”

As Luther bowed and turned to leave, the hall erupted in a buzz of conversation. Some called him a coward for not answering immediately. Others whispered that his request showed wisdom. But all agreed that the stakes had somehow grown even higher. Tomorrow’s session would be the real confrontation.

Luther made his way through the crowd, feeling their stares like physical blows. Some faces showed curiosity, others contempt, still others a kind of fascinated horror, as if they were watching a man walking voluntarily toward his own execution.

Outside the palace, the narrow streets of Worms were packed with people who had traveled from across the empire to witness these proceedings. Word of Luther’s request for delay spread through the crowd like ripples in a pond, generating fierce debates on every corner.

In his modest lodgings, Luther found his small circle of supporters waiting with faces full of desperate hope and barely contained fear. Spalatin paced the cramped room like a caged animal, while two other supporters from Wittenberg sat in chairs pulled close to the single window, as if proximity to the outside world might somehow provide escape from their predicament.

“Well?” Spalatin demanded before Luther had even closed the door. “What happened? We could hear the crowd’s reaction from here, but no clear word of what transpired.”

Luther sank into the room’s only remaining chair, suddenly feeling every one of his thirty-seven years. “They want me to recant everything — every book, every sermon, every word I’ve written about papal corruption and justification by faith alone.”

“And your response?”

“I asked for time to consider.”

The silence that greeted this announcement was deafening. Finally, one of the Wittenberg supporters found his voice: “You asked for time? Martin, surely you knew what your answer would be before you entered that hall?”

Luther looked up at his friends, seeing in their faces a reflection of his own internal turmoil. “Did I? Did any of us truly understand what this moment would demand? It’s easy to be defiant in one’s study, surrounded by books and loyal students. It’s quite another thing to stand before the assembled might of the Holy Roman Empire and choose death over compromise.”

“But you cannot seriously be considering recantation?” Spalatin’s voice carried a note of panic. “Everything we’ve worked for, everything you’ve taught — “

“Everything I’ve taught,” Luther interrupted, “assumes that I’ve been right. But what if I’ve been wrong? What if my rebellion against papal authority has been pride masquerading as principle? What if I’ve led thousands of souls astray through my stubborn refusal to submit to legitimate church authority?”

The question hung in the air like an accusation. These men had followed Luther’s lead, had staked their own reputations and futures on his theological insights. The possibility that their leader might be having second thoughts was almost too terrible to contemplate.

Outside, the sounds of the city continued — merchants hawking their wares, horses clattering over cobblestones, the ordinary business of life proceeding as if the foundations of Christendom were not trembling on the edge of collapse.

As darkness fell over Worms, Luther knelt alone in his chamber, wrestling with the most momentous decision of his life. Tomorrow he would stand again before emperor and princes, and his words would echo through history. The only question was what those words would be.

In the palace, Emperor Charles stared out at the same darkness, wondering if his empire would survive whatever tomorrow would bring. And in chambers throughout the city, princes and bishops, merchants and scholars, all prepared for a confrontation that would reshape the spiritual landscape of Europe.

“Here I Stand”

The Speech That Shattered a Thousand Years

The dawn brought no peace to Martin Luther’s tormented soul. He had spent the night on his knees, alternating between desperate prayer and careful study of the Scriptures that had first opened his eyes to what he saw as Rome’s corruption. Now, as pale morning light filtered through the narrow window of his chamber, he faced the most crucial hours of his life.

His small Bible lay open before him to Romans, chapter one: “For I am not ashamed of the gospel of Christ: for it is the power of God unto salvation to every one that believeth.” The words seemed to pulse with life on the page, and Luther felt something crystallizing in his chest — not the absence of fear, but something stronger than fear.

A knock at his door interrupted his meditation. Spalatin entered without waiting for permission, his face drawn with sleepless anxiety.

“The entire city is talking of nothing else,” he reported. “Some say you’ll recant to save your life. Others claim you’ll die before compromising a single word. The betting houses are taking wagers on the outcome.”

Luther looked up from his Bible with eyes that seemed somehow different — clearer, more focused than they had been the day before. “And what do you say, Georg? What does your heart tell you I will do?”

Spalatin studied his friend’s face, searching for some clue to his intentions. “Yesterday, I would have sworn you would never yield. But seeing you in that hall, witnessing the power arrayed against you… I confess I no longer know what to expect.”

“Then you understand my struggle perfectly,” Luther replied, closing the Bible with reverent care. “For I have spent this night discovering what I truly believe, stripped of all academic pride and worldly consideration. The question is not what Martin Luther wants to do, but what God requires of His servant.”

Before Spalatin could respond, another knock came at the door. This time it was a herald in imperial colors, bearing the formal summons to appear before the Diet. The moment of reckoning had arrived.

As Luther made his way through the crowded streets toward the palace, word of his approach spread like wildfire. People pressed against the buildings to catch a glimpse of the man who had challenged the Pope himself. Some called out blessings, others curses. Children were lifted onto shoulders for a better view, and more than one merchant closed his shop to follow the procession.

“Look at him,” whispered a baker to his neighbor. “Does he look like a man going to his death, or a man going to battle?”

Indeed, Luther’s bearing had changed dramatically from the previous day. Gone was the trembling uncertainty, replaced by something that seemed almost like serenity. His step was firm, his gaze direct, and there was an quality about him that made even his critics pause.

Inside the great hall, the atmosphere was electric with anticipation. If anything, the crowd was even larger than before, with additional benches hastily constructed to accommodate the overflow. Emperor Charles sat rigidly upright on his throne, having spent his own sleepless night wrestling with the political implications of whatever was about to unfold.

Cardinal Aleander leaned forward in his seat, his sharp eyes fixed on the approaching figure. He had orchestrated the downfall of other heretics, but something about Luther’s demeanor sent an unwelcome chill down his spine. This was not how condemned men usually walked to their judgment.

Frederick the Wise watched his protégé with the intensity of a father watching his son face a deadly trial. Everything the Elector had worked for — his careful balance between reform and rebellion, his protection of learning and scholarship — hung in the balance of the next few minutes.

Johann Eck rose from his seat with theatrical precision, the stack of Luther’s works still prominently displayed on the table before him. As papal representative, he held the power to offer mercy for recantation or demand punishment for continued defiance. His face bore the satisfied expression of a hunter who had cornered his prey.

“Martin Luther,” Eck’s voice rang across the hushed assembly, “yesterday you were granted time to consider your answer to a simple question. Do you defend all these books and their contents, or are you prepared to retract any part of them?”

Luther stepped forward until he stood directly before the table bearing his life’s work. For a long moment, he simply looked at the volumes — thirty books that represented years of study, prayer, and careful reasoning about the nature of salvation and the corruption he perceived in the Church hierarchy.

When he finally spoke, his voice carried clearly to every corner of the vast hall, steady and sure despite the magnitude of the moment.

“Most Serene Emperor, Most Illustrious Princes, Most Gracious Lords,” he began, his formal address acknowledging the dignity of his audience while maintaining his own. “I appear before you today by virtue of your summons, and I pray that Your Imperial Majesty and Your Lordships will hear me with clemency.”

A murmur rippled through the assembly. Luther’s tone was respectful but not subservient, courteous but not cowering.

“The books acknowledged as mine yesterday can be divided into three categories,” Luther continued, his scholarly mind organizing his defense with the precision that had made him one of Germany’s most respected theologians.

“First, there are those works in which I have written of Christian faith and morals so simply and evangelically that even my enemies are compelled to admit they are useful, harmless, and worthy to be read by Christians. Even the papal bull condemning me acknowledges that some of my books contain good material. Surely it would be madness to retract these works which find approval even from my adversaries?”

Eck’s face darkened. This was not the simple yes-or-no answer he had expected. Luther was mounting a systematic defense, turning his condemnation into a theological debate.

“Second,” Luther pressed on, his confidence growing with each word, “I have written books against the papacy and papal doctrine, exposing those who by their evil teaching and example have devastated the Christian world with spiritual and temporal ruin. No one can deny this, for universal experience and worldwide complaint testify that the Pope’s laws and human traditions have entangled, tormented, and torn to pieces the consciences of the faithful.”

A shocked silence greeted these words. Luther was not retreating — he was advancing, using this moment of supreme vulnerability to launch his most direct attack yet on papal authority.

In the front row, Cardinal Aleander half-rose from his seat, his face flushed with indignation. Never had he heard such bold accusations delivered directly to the assembled representatives of Christendom.

Emperor Charles leaned forward, his young face tense with concentration. This was not the cringing recantation he had been led to expect, nor was it the simple defiance that would have made Luther’s condemnation straightforward. This was something far more dangerous — a reasoned, systematic challenge to the very foundations of medieval Christianity.

“Shall I then retract these works?” Luther asked, his voice rising with passion. “If I do so, I shall be the only man on earth to strengthen tyranny and open the windows to such great godlessness. The tyranny will become more severe and unbearable than ever, especially since it will be seen that I — encouraged by Your Most Serene Majesty and the illustrious German nobility — have recanted.”

The hall was utterly silent now, every person straining to catch Luther’s words. History was being made with each sentence, and everyone present could feel the weight of the moment.

“Third, I have written books against certain private individuals who have tried to defend Roman tyranny and undermine my efforts at reform. I confess I have been more harsh in these writings than befits my station or Christian charity. But I cannot retract these either, for to do so would be to grant immunity to tyranny and impiety, allowing them to rage more freely than ever against God’s people.”

Luther paused, his eyes sweeping across the assembly, meeting the gaze of emperor and peasant alike with equal directness.

“However,” he continued, and the entire hall seemed to hold its breath, “since I am a man and not God, I cannot defend my books any differently than my Lord Jesus Christ defended His teaching. When questioned by Annas, He said: ‘If I have spoken evil, bear witness of the evil.’ If our Lord, who could not err, made this request, how much more should I, who am the least of men and capable of nothing but error, ask that someone prove my teaching contrary to Scripture?”

The challenge was unmistakable. Luther was not simply defending his works — he was demanding that his accusers prove them wrong using Scripture alone, not papal authority or church tradition.

Johann Eck could contain himself no longer. “You ask for Scripture?” he interjected, his voice sharp with indignation. “The Church has interpreted Scripture for over a thousand years. Do you claim to understand God’s Word better than all the saints and doctors who have gone before?”

Luther turned to face his longtime adversary, and for a moment the two men stared at each other across an ideological chasm that seemed to span eternity.

“I trust no one’s interpretation above Scripture itself,” Luther replied firmly. “Popes have erred, councils have erred, church fathers have erred. Only Scripture is infallible, and to Scripture alone I submit my conscience.”

The words struck the assembly like thunderbolts. Luther had just rejected not only papal authority but the entire structure of medieval Christianity, with its reliance on tradition and ecclesiastical interpretation.

Emperor Charles felt the implications washing over him like a cold tide. If Luther was right, then a thousand years of Christian civilization had been built on false foundations. If he was wrong, then he was the most dangerous heretic in history. Either way, the unity Charles desperately sought for his empire was crumbling before his eyes.

Eck made one final attempt to salvage the situation. “Will you recant or not? Give us a simple answer without horns!”

Luther straightened to his full height, and when he spoke, his voice carried a quiet authority that seemed to fill every corner of the vast hall.

“Since Your Imperial Majesty and Your Lordships seek a simple answer, I shall give it, with no horns and no teeth. Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason — for I do not accept the authority of popes and councils alone, since it is established that they have often erred and contradicted themselves — I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted, and my conscience is captive to the Word of God.”

He paused, and in that moment of silence, the fate of European Christianity hung in the balance.

“I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe.” His voice rose to a clarion call that seemed to echo from the very stones of the ancient hall: “Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise. God help me. Amen.”

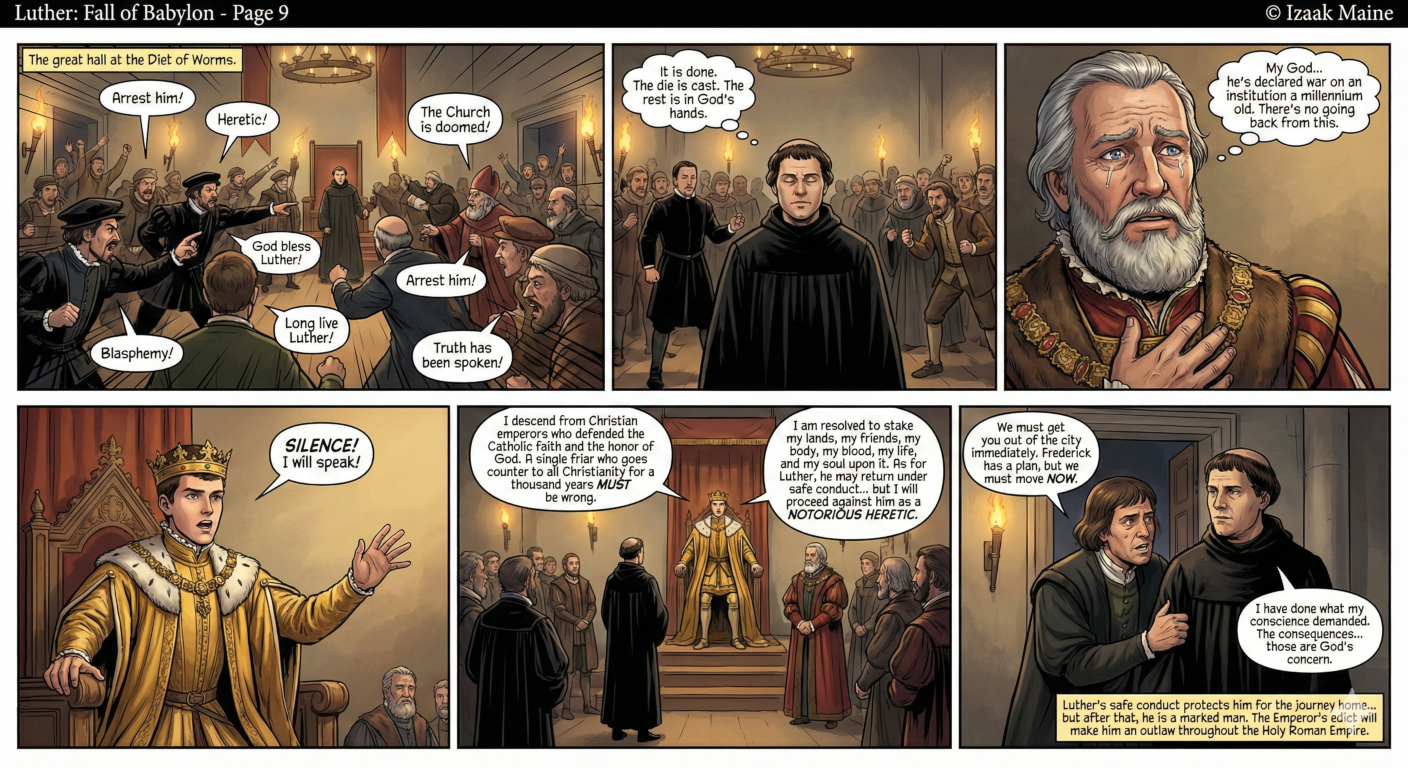

The words fell into absolute silence like stones into still water. For a heartbeat, no one moved, no one breathed. Then the hall erupted into chaos.

Spanish courtiers shouted in outrage while German nobles murmured among themselves. Some bishops called for Luther’s immediate arrest, while others seemed stunned into silence. In the midst of the uproar, Emperor Charles sat motionless on his throne, his young face grave with the weight of decision.

Luther stood unmoved in the center of the storm, his declaration hanging in the air like a banner. He had crossed the Rubicon now, had burned his bridges behind him. There could be no retreat from this moment, no compromise with the forces arrayed against him.

Frederick the Wise felt his heart hammering against his ribs. His protégé had just declared war on an institution that had dominated Europe for a millennium. The political implications were staggering, the potential for violence terrifying.

But even as chaos swirled around him, Luther felt a strange peace settling over his spirit. The long struggle with doubt was over. He had spoken the truth as he understood it, had followed his conscience despite the consequences. Whatever happened now was in God’s hands.

Emperor Charles finally raised his hand for silence, and gradually the tumult died away. When he spoke, his voice carried the full authority of his imperial office.

“This man will never make me a heretic. I descend from a long line of Christian emperors of this noble German nation, and of the Catholic kings of Spain, the archdukes of Austria, and the dukes of Burgundy. They were all faithful to the death to the Church of Rome, and they defended the Catholic faith and the honor of God. After their death they left, by natural and divine right, these holy Catholic observances for me to live and die by, following their example.”

The emperor’s words fell like hammer blows, each sentence sealing Luther’s fate more completely.

“A single friar who goes counter to all Christianity for a thousand years must be wrong. Therefore, I am resolved to stake my lands, my friends, my body, my blood, my life, and my soul upon it.”

Charles rose from his throne, his young frame somehow carrying the weight of centuries of imperial authority. “As for Luther, I regret that I have so long delayed proceeding against him and his false teaching. I will have no more to do with him. He may return under his safe conduct, but without preaching or making any tumult. I will proceed against him as a notorious heretic, and ask that you do the same.”

The pronouncement struck the assembly like a physical blow. Luther had been declared a notorious heretic by the Holy Roman Emperor himself. The safe conduct would protect him on his journey home, but after that, he would be fair game for any who wished to claim the reward for his capture.

As the formal session dissolved into urgent conferences and whispered conversations, Luther found himself surrounded by a small knot of supporters. Spalatin gripped his arm with desperate intensity.

“We must get you out of the city immediately,” he whispered urgently. “Frederick has a plan, but it requires us to move quickly.”

Luther nodded, though his mind seemed strangely detached from the immediate danger. He had done what his conscience demanded, had spoken truth to power in its most concentrated form. The consequences would unfold as God willed.

As they made their way through the crowded streets toward Luther’s lodgings, word of the confrontation spread like wildfire. Groups of people gathered on corners, some praising Luther’s courage, others denouncing his heresy. The very air seemed to crackle with tension, as if the city itself might explode into violence at any moment.

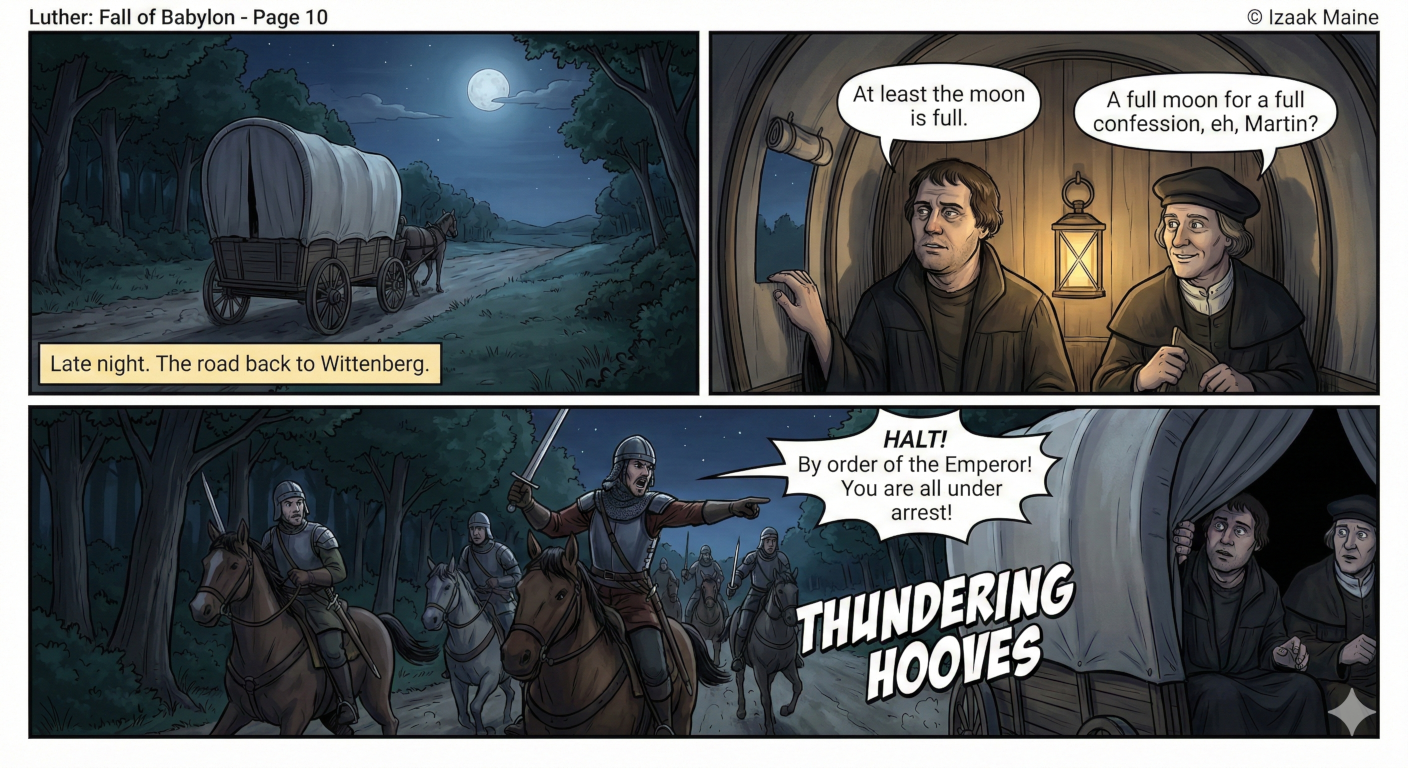

Within hours, Luther’s small party was on the road back toward Saxony, traveling under the emperor’s safe conduct but knowing that protection would expire the moment they crossed certain boundaries. The journey that had begun with a terrified monk riding toward possible martyrdom was ending with a declared heretic fleeing toward an uncertain exile.

But as their wagon rolled through the German countryside, Luther felt no regret for the words he had spoken. He had stood before the assembled might of the old order and declared his allegiance to a higher authority. The medieval world might condemn him, but he had planted seeds that would grow into something entirely new.

Behind them, in the great hall where Luther had made his stand, Emperor Charles stared out at an empire that would never be the same. The unity he had sought to preserve had been shattered by one man’s refusal to compromise his conscience. The future stretched ahead like an uncharted sea, full of storms and possibilities that no one could foresee.

The Reformation had begun in earnest, born from the collision between individual conviction and imperial authority. And at its heart lay those simple, revolutionary words that would echo through the centuries: “Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise. God help me. Amen.”

The fire of conviction, once kindled, could never be completely extinguished.