The Debate at Valladolid

In 1550, Spain did the unthinkable—it halted its conquest of the Americas to stage a philosophical showdown between a hardened theologian who had never crossed the Atlantic and a prophetic friar who had witnessed forty years of colonial hell, with the fate of millions hanging on their words. Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda wielded Aristotle like a sword, arguing that Indigenous peoples were “slaves by nature” who benefited from subjugation, while Bartolomé de las Casas thundered back with testimonies of genocide, insisting that those being slaughtered for gold possessed souls as sacred as any Spaniard’s. The Valladolid Debate produced no clear victor and changed little immediately, yet it cracked open a question that would haunt empires for centuries: what happens when a civilization conquering the world is forced, if only for a moment, to examine whether its butchery has a philosophical defense—or whether it is simply butchery dressed in syllogisms?

Chapter One: The Weight of Gold

The ship creaked as it cut through Atlantic waters, carrying Father Bartolomé de las Casas back to Spain in 1547. He stood at the railing, his Dominican robes whipping in the salt wind, watching the New World disappear behind him. In his cabin lay manuscripts that would burn like coals in the hands of the royal court—testimonies of what Spain had wrought across the ocean.

He had been young once, an encomendero himself, collecting tribute from the Taíno people assigned to his estate in Cuba. He remembered their faces as they brought him cassava and gold dust, remembered thinking this was the natural order of things. The year 1514 had changed him. Preparing a sermon for Pentecost, he had read Ecclesiasticus: “The bread of the needy is their life; he that defrauds them thereof is a man of blood.” The words had seized him like a hand around his throat.

The islands were graveyards now. Where hundreds of thousands had lived, only thousands remained. The encomienda system—that elegant administrative solution that gave Spanish settlers “guardianship” over Indigenous populations—had proven itself a mechanism of annihilation. The guardians worked their wards to death in mines and fields, replaced them with new shipments of souls, and enriched themselves beyond measure.

Meanwhile, in Córdoba, Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda sat in his study surrounded by leather-bound volumes of Aristotle, Aquinas, and Augustine. At sixty-seven, he was Spain’s most formidable philosopher-theologian, a man whose Latin prose was as sharp as Toledo steel. He had never crossed the Atlantic, had never seen the peoples he wrote about, but he understood them perfectly through the lens of philosophy.

The reports from the New World troubled him not for their brutality but for their inefficiency. The conquest was just—this he knew with the certainty of logical proof—but it was being prosecuted with insufficient intellectual rigor. Too many conquistadors simply killed and plundered without understanding the philosophical necessity of their actions.

Sepúlveda dipped his quill and wrote: “The Spanish have a perfect right to rule these barbarians of the New World and the neighboring islands, who in prudence, skill, virtues, and humanity are as inferior to the Spanish as children to adults, or women to men.”

He paused, considering. The argument needed sharpening. Aristotle had provided the foundation in his Politics: some men are slaves by nature, lacking the rational capacity for self-governance. They benefit from subjugation to superior intellects as the body benefits from the rule of the soul. The evidence from the Americas confirmed the Greek philosopher’s wisdom across two thousand years.

The Indigenous peoples practiced human sacrifice and cannibalism—abominations that placed them outside the natural law. They lived without proper governance, without written language, without understanding of property or commerce. Most damningly, they had dwelt in darkness without knowledge of Christ until Spanish missionaries brought them salvation at sword-point.

“War against these barbarians can be justified,” he wrote, “not only on account of their idolatry and other sins against nature, but also to pave the way for the preaching of the Christian religion and to facilitate its acceptance.”

In Seville, las Casas gathered witnesses. Former soldiers spoke of villages burned, of children run through with pikes for sport, of dogs trained to tear Indigenous flesh. A merchant described how the price of a slave had fallen so low that men traded them for cheese. A reformed encomendero wept as he recounted ordering a nursing mother beaten for working too slowly, her infant wailing beside her.

Las Casas transcribed it all. His Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies grew into a document of apocalyptic horror. “They violently forced away Women and Children to make them Slaves, and ill-treated them,” he wrote, his hand trembling with rage, “consuming and wasting their Food, which they had purchased with great sweat, toil, and yet remained dissatisfied too.”

The numbers haunted him. Hispaniola alone—three million souls reduced to a few thousand. Cuba, Jamaica, the Bahamas—entire peoples extinguished like candle flames. And now the conquistadors were pushing into Mexico and Peru, bringing the same methods to empires of millions.

He secured an audience with Charles V’s advisors. The young emperor’s conscience was troubled by reports from across his vast dominions. The New World was producing unprecedented wealth—silver from Potosí, gold from New Granada—but at what cost to Spain’s immortal soul?

The Council of the Indies listened to las Casas with growing discomfort. Here was a friar with decades of New World experience, speaking with the authority of witness. But his demands were radical: abolish the encomienda, punish the conquistadors, grant Indigenous peoples the protection of Spanish law. The economic implications were staggering.

Word of the controversy reached Sepúlveda. He saw immediately that the empire stood at a crossroads. Either the conquest would be affirmed as philosophically just and morally necessary, or Spain would falter in its divine mission to bring Christianity and civilization to the barbarian world. Las Casas, with his bleeding-heart sentimentality, threatened to undermine decades of expansion.

Sepúlveda requested permission to publish his treatise Democrates Alter, which laid out the philosophical case for just war against the Indigenous peoples. The request was denied—the arguments were too inflammatory, the timing too sensitive. But whispers of the debate spread through the universities and monasteries.

In 1550, Charles V made an extraordinary decision. He would convene a formal disputation between las Casas and Sepúlveda to settle the matter. The venue: Valladolid, in the Colegio de San Gregorio. The judges: fourteen theologians and councilors of the realm. The question: whether the wars of conquest in the New World were just, and whether the Indigenous peoples could be enslaved.

Spain, for perhaps the first time in the Age of Exploration, would pause to examine its own soul.

Chapter Two: The Journey to Judgment

The summer heat lay thick over Valladolid as the participants gathered in August 1550. The Colegio de San Gregorio rose like a fortress of learning, its elaborate façade carved with vines and shields, its halls echoing with centuries of theological disputation. But never had it hosted a debate with such implications—the fate of millions hanging on syllogisms and Scripture.

Sepúlveda arrived with an economy of luggage but an abundance of texts. Aristotle’s Politics, of course. Augustine’s City of God. Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologica. He had organized his arguments into four principal demonstrations, each building inexorably toward the conclusion that the conquest was not merely permissible but morally obligatory.

In the refectory, he encountered some of the judges: Domingo de Soto, a Dominican theologian of fierce intellect; Melchor Cano, who had studied under Francisco de Vitoria; Bartolomé de Carranza, soon to be Archbishop of Toledo. These were serious men, not easily swayed by emotion.

“The question before us,” Sepúlveda told them over wine that first evening, “is not whether abuses have occurred. War always produces excesses. The question is whether the war itself is just in principle.”

Las Casas arrived like an Old Testament prophet, gaunt from decades of tropical fevers and righteous anger, his arms laden with manuscripts. He had written a new work specifically for this occasion—a massive treatise running to hundreds of pages, defending the rationality and humanity of the Indigenous peoples. Three assistants helped carry his documentation: testimonies, letters, royal decrees, and his own observations from forty years in the Americas.

He took simple lodgings near the college. The evening before the debate began, he knelt in prayer until his knees ached. “Grant me,” he whispered, “not eloquence but truth. Not victory but justice.”

The format was unusual. Rather than a single day of disputation, the debate would unfold across multiple sessions, allowing each side to present comprehensive arguments. Sepúlveda would speak first, laying out the philosophical framework. Las Casas would respond, then Sepúlveda would offer rebuttals.

On the first day, the judges assembled in the great hall. Tapestries depicting biblical scenes covered the stone walls. August light filtered through high windows, illuminating the space where intellectual combat would occur.

Sepúlveda rose. He was a smaller man than las Casas, compact and precise in his movements. His Latin was exquisite, each phrase balanced like an equation.

“Illustrious judges,” he began, “I come before you to demonstrate four truths. First, that the barbarians of the New World, by reason of their grievous sins against natural law, particularly their idolatry and human sacrifice, may justly be warred upon. Second, that their rudeness and inferior nature obligates them to serve those of superior prudence and virtue. Third, that war facilitates the propagation of the Christian faith. Fourth, that war protects innocent victims of their barbarous practices.”

He warmed to his subject, his voice gaining strength. “Aristotle teaches us that some men are slaves by nature—those who lack sufficient reason to govern themselves but possess enough to receive direction from others. Such men benefit from subjection to wiser masters as the body benefits from the mind’s governance.”

The evidence, Sepúlveda argued, was overwhelming. The Indigenous peoples had no written language, no complex legal systems, no understanding of commerce or philosophy. They built no proper cities—their settlements were crude compared to Toledo or Salamanca. They wore minimal clothing, lived without shame, and followed leaders who were little more than tribal chieftains.

“Consider their religious practices,” he said, his voice dropping to convey horror. “They tear the beating hearts from living victims atop their pyramids. They practice cannibalism, devouring human flesh in rituals of unspeakable depravity. They worship demons in the form of serpents and jaguars. These are not the acts of rational men but of beasts who possess a semblance of humanity.”

He paced as he spoke, making eye contact with each judge. “Some say we should preach to them peacefully, win them through gentleness. But how does one reason with those who lack reason? How does one persuade those who sacrifice children to idols? Scripture itself commands the destruction of the Canaanites for lesser abominations.”

“The Spanish conquest,” Sepúlveda concluded his first presentation, “is not merely just—it is merciful. We save the innocent from slaughter. We bring the light of Christ to those dwelling in darkness. We elevate inferior peoples by placing them under the governance of the superior. To hesitate in this sacred duty would be to abandon both divine commandment and natural law.”

The judges murmured among themselves. The argument was formidable, built on foundations that had supported Western thought for millennia. Aristotle and Aquinas were not easily dismissed.

Las Casas stood. At seventy-six, he seemed carved from oak, weathered but unbreakable. Unlike Sepúlveda’s measured tones, las Casas spoke with the passion of a man who had seen hell opened upon earth.

“My lords,” he began, “my opponent speaks of philosophy and I will answer with philosophy. But I speak also as witness to what our people have done across the ocean, and that testimony cannot be dismissed by syllogisms alone.”

He held up a manuscript. “I have here documented the destruction of Hispaniola. Not through war—for the Taíno offered no resistance worthy of the name—but through cruelty born of greed. They were tortured for gold they did not possess. Worked to death in mines to fill Spanish coffers. Hunted with dogs like animals when they fled into the mountains.”

His voice rose. “Dr. Sepúlveda speaks of human sacrifice, and yes, some peoples practiced this evil. But we have slaughtered more innocents in forty years than they sacrificed in forty generations. We have depopulated entire islands. We have orphaned countless children and widowed countless women. And we call this justice?”

Las Casas turned to face Sepúlveda directly. “You say they lack reason, that they are slaves by nature. I have lived among them. I have learned their languages. I have seen their governance, their art, their family bonds. They reason as we reason. They love as we love. They grieve as we grieve.”

The debate continued for days, then weeks, stretching into September. Sepúlveda maintained his philosophical high ground, returning again and again to Aristotle and natural law. Las Casas battered at that ground with specific atrocities, with testimonies, with appeals to Christian mercy.

The judges listened, questioned, deliberated. Spain held its breath.

Chapter Three: The Reckoning

Mid-September brought cooling winds to Valladolid, but the atmosphere in the Colegio de San Gregorio remained heated. The debate had evolved into something unprecedented—not a simple disputation but an examination of Spain’s entire colonial enterprise, and by extension, the nature of humanity itself.

Sepúlveda had refined his arguments through the sessions, addressing each of las Casas’s objections with methodical precision. On the seventh day of formal debate, he presented what he considered his decisive proof.

“The friar speaks of atrocities,” Sepúlveda acknowledged, “and I do not doubt that excesses have occurred. But these are failures of individual Spaniards, not failures of the conquest itself. A just war justly executed may still be prosecuted unjustly by evil men. This does not invalidate the war’s fundamental justice.”

He approached the core of his argument. “The Indigenous peoples engage in practices that violate natural law so profoundly that they place themselves outside the protection of that law. Human sacrifice is not merely wrong—it is an inversion of the proper order of creation. Those who tear hearts from living victims and offer them to demons have rejected reason itself.”

One of the judges, Domingo de Soto, interrupted. “But Doctor, does not the Christian faith teach that God’s grace can transform any soul? Did not Saint Paul himself persecute Christians before his conversion?”

Sepúlveda smiled slightly. “Indeed, Father Domingo. Which is precisely why the conquest serves divine purposes. We cannot preach to those who kill our missionaries. We cannot baptize those who flee into jungles to continue their abominations. First must come pacification, then instruction, then salvation. The sword prepares the way for the cross.”

“You speak of their lack of civilization,” he continued, “and compare their cities to ours. But I invite you to consider what Aristotle meant by civilization. It is not mere building of structures but the cultivation of virtue through proper governance. The Greeks built magnificently, yet Aristotle deemed some Greeks naturally servile. How much more so these peoples who, despite some crude accomplishments, practice evils the Greeks would have found abhorrent?”

Las Casas requested permission to respond immediately rather than waiting for the next session. The request was granted.

He stood slowly, and when he spoke, his voice was quiet, forcing the judges to lean forward.

“Dr. Sepúlveda has never set foot in the New World,” he said. “He knows these peoples only through reports filtered through conquistadors and encomenderos—men whose wealth depends on Indigenous slavery. Would you trust a slave trader’s description of those he enslaves?”

Las Casas walked to the center of the hall. “I have lived forty years among the peoples my opponent calls barbarians. Let me tell you what I have witnessed. In Mexico, I saw cities that would rival Rome in their organization and grandeur. I saw markets where commerce was conducted with a sophistication that would impress any Venetian merchant. I saw legal proceedings that demonstrated understanding of justice and evidence.”

He pulled out a manuscript. “I have documented here the languages of various Indigenous nations. They are not grunts and gestures but sophisticated tongues with grammar and vocabulary capable of expressing complex philosophical concepts. The Nahuatl language has forms for expressing degrees of respect and relationship that Spanish lacks. Does this suggest inferior reason?”

“As for human sacrifice,” las Casas continued, his voice hardening, “yes, some peoples practiced this evil. But remember that our own ancestors practiced human sacrifice before Christianity reached them. Were the Romans and Celts slaves by nature? Should they have been conquered and enslaved by whoever first achieved civilization?”

Melchor Cano, one of the judges, interjected. “But Father Bartolomé, surely you do not equate the sacrifice practices of the Mexica with occasional aberrations in European history?”

“I equate nothing,” las Casas replied. “I simply observe that peoples can abandon evil practices through instruction and example rather than through the sword. In Nicaragua, I witnessed peaceful conversion of entire communities. No war was necessary—only patience and genuine Christian charity.”

He turned back to Sepúlveda. “You build your entire argument on Aristotle’s concept of natural slavery. But Aristotle also said that barbarians were those who did not speak Greek. Every people appeared barbarian to those who did not understand them. Natural slavery is a philosophical concept, not an empirical observation. Show me the physical characteristic that distinguishes the natural slave from the natural master. You cannot, because it does not exist.”

Las Casas’s voice rose to a shout. “These are men! They have souls! They reason, they create, they love, they suffer! That some of their practices are evil does not make them slaves by nature any more than the Spanish Inquisition’s burnings make Spaniards slaves by nature!”

The hall fell silent. Las Casas had struck at something profound—the idea that cultural practices could determine essential human nature.

Sepúlveda rose to respond, his composure intact. “The friar makes an emotional appeal, but philosophy requires more than sentiment. Yes, the Indigenous peoples possess souls and reason of a sort. But reason exists in degrees. A child has reason but not sufficient reason for self-governance. A woman has reason but not equal to a man’s in matters of war and politics. The Indigenous peoples have reason but not sufficient reason for complex civilization.”

“The evidence is before us,” Sepúlveda pressed. “When Spaniards arrived in the New World, did they find universities? Did they find libraries? Did they find ships capable of crossing oceans? Did they find philosophical treatises debating the nature of the good? No. They found peoples living in a state of arrested development, capable of crude accomplishments but incapable of true civilization without external guidance.”

Las Casas shook his head vehemently. “They found peoples who had developed separately from Europe, whose accomplishments took different forms but were no less sophisticated. The Inca built roads and administrative systems that spanned thousands of miles without written language—an achievement that demonstrates extraordinary organizational ability. The Maya developed mathematics including the concept of zero, which Europeans learned from the Arabs.”

The debate continued for another week, grinding through theological fine points and philosophical distinctions. Sepúlveda argued that even if the Indigenous peoples were not natural slaves, the need to stop human sacrifice and cannibalism justified war. Las Casas countered that sins against natural law should be addressed through preaching, not conquest, and that the Spanish had committed greater evils than those they claimed to correct.

Finally, in late September, both sides presented their final arguments.

Sepúlveda’s closing was elegant and concise. “Gentlemen, the question before you is simple. Does Spain have the right and obligation to bring civilization and Christianity to peoples dwelling in barbarism and idolatry? Philosophy and Scripture both answer yes. The method may require refinement, the execution may require improvement, but the fundamental justice of the enterprise is unassailable.”

Las Casas, exhausted but unbowed, made his final plea. “My lords, I ask you to see these peoples as God sees them—as souls worthy of salvation, not as resources to be exploited. Our faith teaches that Christ died for all humanity. How then can we claim that some humans are less human than others? The conquest has brought not civilization but devastation, not Christianity but a mockery of Christian values. End the encomienda. Punish those who have committed atrocities. Recognize the Indigenous peoples as equals under law. This is what justice demands.”

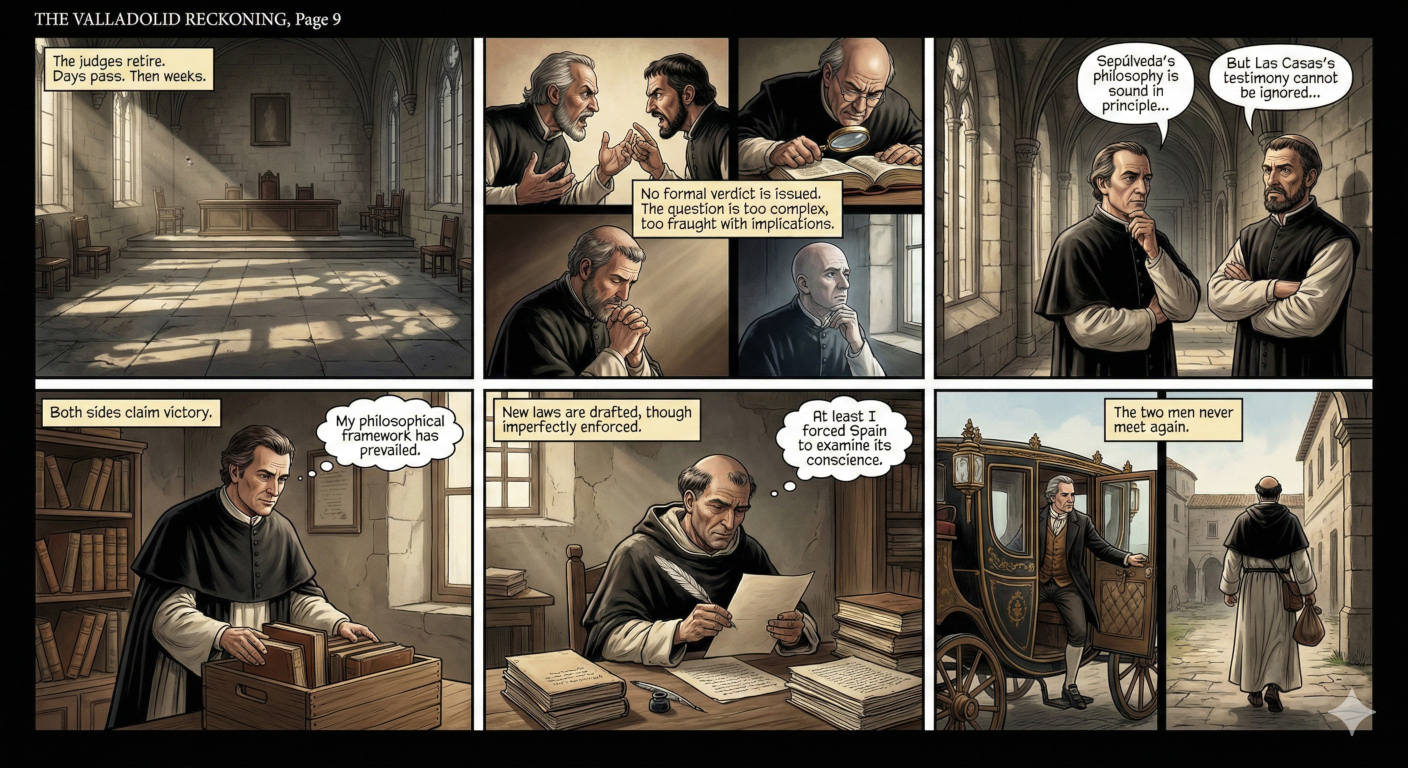

The judges retired to deliberate. Days passed, then weeks. No formal verdict was issued—the question was too complex, too fraught with implications. Some judges sided with Sepúlveda’s philosophical arguments. Others were swayed by las Casas’s testimony and moral passion.

In the end, both sides claimed victory. Sepúlveda believed his philosophical framework had prevailed. Las Casas took comfort in the fact that his arguments had at least forced Spain to examine its conscience. New laws were drafted, though imperfectly enforced. The conquest continued, though with somewhat more restraint.

The two men never met again after Valladolid. Sepúlveda returned to his studies, his faith in Spanish righteousness unshaken. Las Casas continued advocating for Indigenous rights until his death at ninety-two, never ceasing to witness against the horrors he had seen.

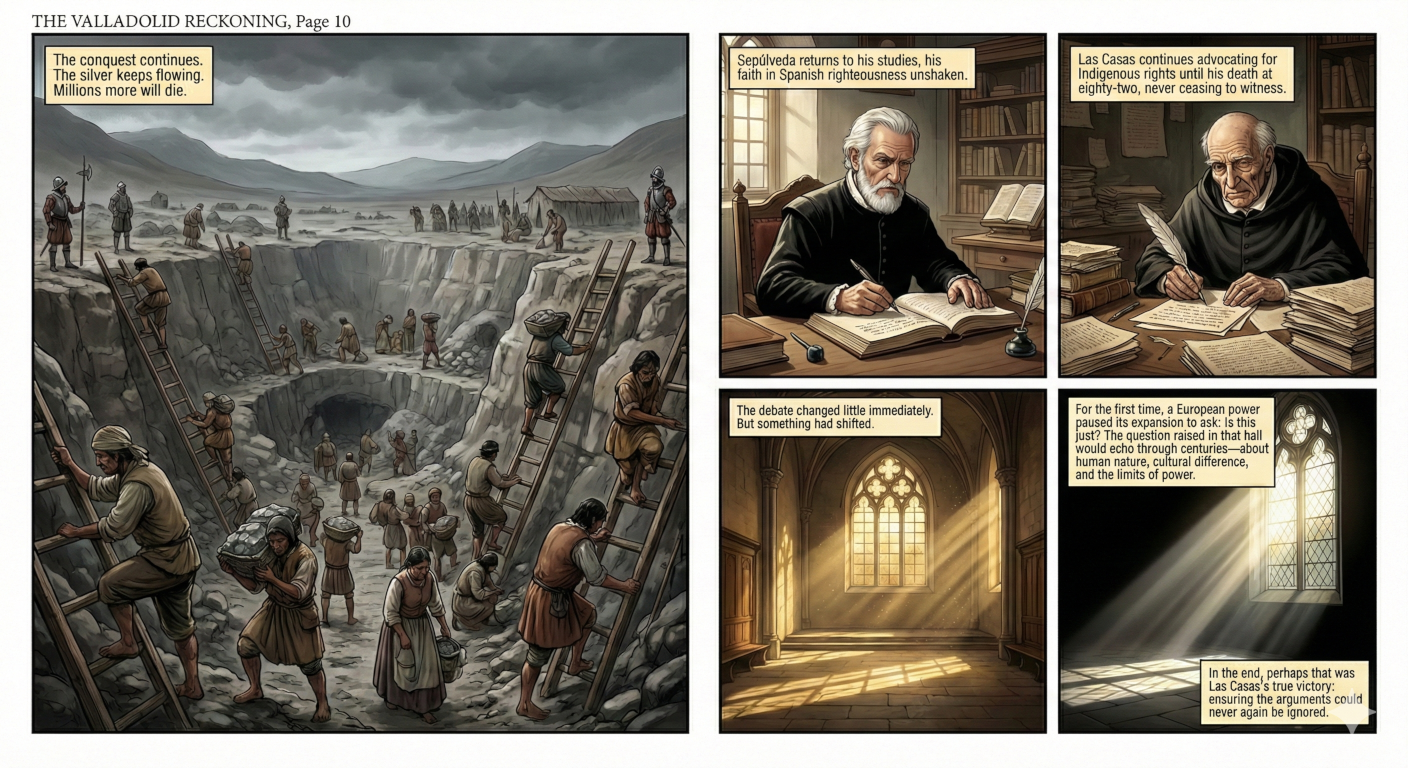

The debate at Valladolid changed little in the short term. The silver kept flowing from Potosí. The encomiendas persisted in various forms. Millions more Indigenous people would die in the centuries of colonial rule that followed.

But something had shifted. For the first time, a European power had paused in its expansion to ask whether that expansion was just. The questions raised in that hall—about human nature, about cultural difference, about the limits of power—would echo through centuries, informing debates about colonialism, slavery, and human rights that continue to this day.

In the end, perhaps that was las Casas’s true victory: not in defeating Sepúlveda’s arguments but in ensuring that the arguments could never again be ignored.