The Longest Way Home

After Ferdinand Magellan died in the Philippines, Basque navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano inherits command of a dying expedition — three rotting ships, 115 starving men, and 9,000 leagues between them and Spain. Through impossible choices that haunt him forever — burning ships, abandoning screaming comrades on beaches, sailing past Portuguese patrols with skeletal crews dying of scurvy — Elcano drags 18 survivors across two oceans, becoming the first humans to circumnavigate the Earth. He returned home in 1522 not as a conqueror but as a haunted man who sacrificed 200+ souls to prove the world was round, earning a coat of arms that read: “You first circumnavigated me” — because the journey didn’t conquer the world; the world conquered him.

Part I: The Weight of Command

The wind off Cebu carried the smell of burning wood and death. Juan Sebastián Elcano stood on the deck of the Trinidad, watching smoke rise from the beach where Ferdinand Magellan’s body lay somewhere among the fallen. April 27th, 1521. The date was seared into his memory like a brand.

“Magellan was a fool,” muttered João Lopes Carvalho, the Portuguese pilot, spitting over the rail. “Charging into a native war like some crusading knight. Now we pay for his madness.”

Elcano said nothing. The Basque navigator had served under Magellan for two years, had challenged him, had even been imprisoned by him during the mutiny at Port San Julian. But watching their captain-general fall to Lapu-Lapu’s warriors had hollowed something inside him. They were three ships and 160 men when they’d left Spain. Now they were three ships and barely 115 souls, stranded on the far side of a world that seemed determined to devour them.

“We must elect new captains,” said Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa, Magellan’s loyal alguacil. His voice cracked. “The fleet cannot survive without command.”

The election was swift, brutal in its pragmatism. Duarte Barbosa and João Serrão took command of the Victoria and Santiago, while Carvalho assumed overall leadership. Elcano remained master of the Concepción, a position he’d held since the mutiny’s aftermath — a kind of redemption for his earlier betrayal.

But redemption, he was learning, was a commodity as scarce as fresh water.

Part II: Betrayal and Blood

May 1st, 1521. The rajah of Cebu, who had welcomed them with feasts and conversion to Christianity, invited the new captains to a banquet on shore. A celebration of alliance, he said. Of friendship between Spain and these islands Magellan had named San Lázaro.

Elcano watched from the Trinidad as the boats rowed toward the beach. Something coiled in his stomach — instinct, perhaps, or the wisdom bought with two years of disasters.

“I don’t like this,” he said to Antonio Pigafetta, the Venetian chronicler who’d become his unlikely confidant. “After Mactan, why would they trust us? Why would we trust them?”

Pigafetta clutched his journal. “Duarte insisted. Said we needed the rajah’s goodwill to resupply.”

The screams started an hour later.

They erupted from the jungle behind the beach — raw, terrible sounds that cut through the tropical afternoon. Elcano was already shouting orders, men scrambling to the rigging, but it was too late. They could see figures fleeing through the trees, natives in pursuit. The boats were too far. The trap was sprung.

“Cut the anchors!” Elcano roared. “Prepare to sail!”

“But the captains — “ someone began.

“Are dead! Move, or we join them!”

Twenty-seven men died on that beach, including Duarte Barbosa and João Serrão. The survivors watched in horror as Serrão was dragged to the waterline, bleeding, begging them to ransom him.

“Please!” His voice carried across the water. “For the love of God, don’t leave me!”

Carvalho, now aboard the Trinidad, stared at the beach, his face like stone. He had a son there, born to a native woman months before. The boy was surely dead too.

“We have no ransom,” Carvalho said finally. “And if we stay, we all die.”

They sailed away to Serrão’s screams. Elcano gripped the rail until his knuckles were white, forcing himself to listen, to remember. This was the price of command. This was what leading meant at the edge of the world.

That night, Pigafetta found him staring at the stars.

“You’re thinking of Serrão,” the Venetian said quietly.

“I’m thinking,” Elcano replied, “that we’re 115 men on three ships with no captain-general, no plan, and half the world between us and home. Magellan promised us glory. He’s given us a floating graveyard.”

“Then what do we do?”

Elcano looked at him. “We survive. And we sail west.”

Part III: The Arithmetic of Death

They limped through the Philippine archipelago like wounded animals, trading desperately for food, repairing sails torn by storms. At Palawan, they elected Carvalho as captain-general, though the Portuguese pilot was losing his grip on sanity, haunted by the son he’d left behind.

By July, a harder truth emerged. They didn’t have enough men to sail three ships.

“We must burn one,” Elcano said at the council. They’d gathered on the Victoria — eighteen officers, all that remained of Spain’s grand expedition. “The Concepción is taking on water faster than we can pump. She’s finished.”

“Burn a king’s ship?” Carvalho’s eyes were wild. “You’d have us destroy Spanish property?”

“Spanish property?” Elcano stood, and his voice cut like a blade. “Look around you, Carvalho. We’re dying. We’re 9,000 leagues from Seville with two ships we can barely crew and a hold full of cloves that means nothing if we’re all dead. The Concepción is a coffin. I won’t let her drag us to the bottom.”

Gómez de Espinosa, ever pragmatic, nodded slowly. “Elcano is right. We transfer her cargo and supplies to the Trinidad and Victoria. Then we burn her.”

They wept as she burned. Even Elcano, who’d given the order, felt tears on his cheeks as the flames climbed her masts. Each ship was a universe unto itself, a piece of home. Watching her sink was like cutting off a limb.

“Two ships,” Pigafetta wrote in his journal that night, his hand shaking. “And 108 men. God have mercy on us.”

Part IV: The Spice Islands

November 8th, 1521. Tidore. The Spice Islands.

The scent hit them first — cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, all the treasures that had launched a thousand ships. The Sultan of Tidore welcomed them like prophets, enemies of the Portuguese who controlled the neighboring island of Ternate. Here, finally, was the prize Magellan had promised.

They loaded 50 tons of cloves into both ships, bartering with knives, cloth, and mirrors. For three months, they rested, repaired, and prepared for the voyage home. But the ships themselves presented a dilemma.

“The Trinidad is finished,” Espinosa said one evening. They stood on the beach, watching shipwrights work on the leaking hull. “Her timbers are rotted through. She won’t survive the Indian Ocean.”

Carvalho had grown increasingly erratic, and in February 1522, the men voted him out. They elected Espinosa to command the Trinidad — she would sail east back across the Pacific, catching favorable winds back to New Spain. The Victoria, smaller but sounder, would dare the western route: across the Indian Ocean, around Africa, home to Spain.

They needed a captain for the Victoria. Someone hard enough to make impossible choices. Someone who’d already proven he would sacrifice anything to survive.

“Elcano,” said Espinosa simply. “Take the Victoria. Take her home.”

Juan Sebastián Elcano, mutineer and navigator, looked at the caravel that would be his salvation or his tomb. Forty-seven souls would sail with him. The rest — sixty men — would try the Pacific with Espinosa.

He gripped his friend’s arm. “When we meet in Spain, the wine is on me.”

Espinosa smiled, but his eyes were ancient. “When we meet in Spain, my friend, we’ll know we’ve witnessed a miracle.”

They sailed on December 21st, 1521. The Trinidad and Victoria fired salutes, then turned away from each other — one east, one west. They would never meet again. The Trinidad would founder in the Pacific, her crew captured by the Portuguese. Only four would ever make it back to Spain, years later, broken men with stories no one believed.

But Elcano didn’t know this yet. He knew only the vast, hostile Indian Ocean ahead.

Part V: The Devil’s Ocean

The Indian Ocean was a beast with many mouths.

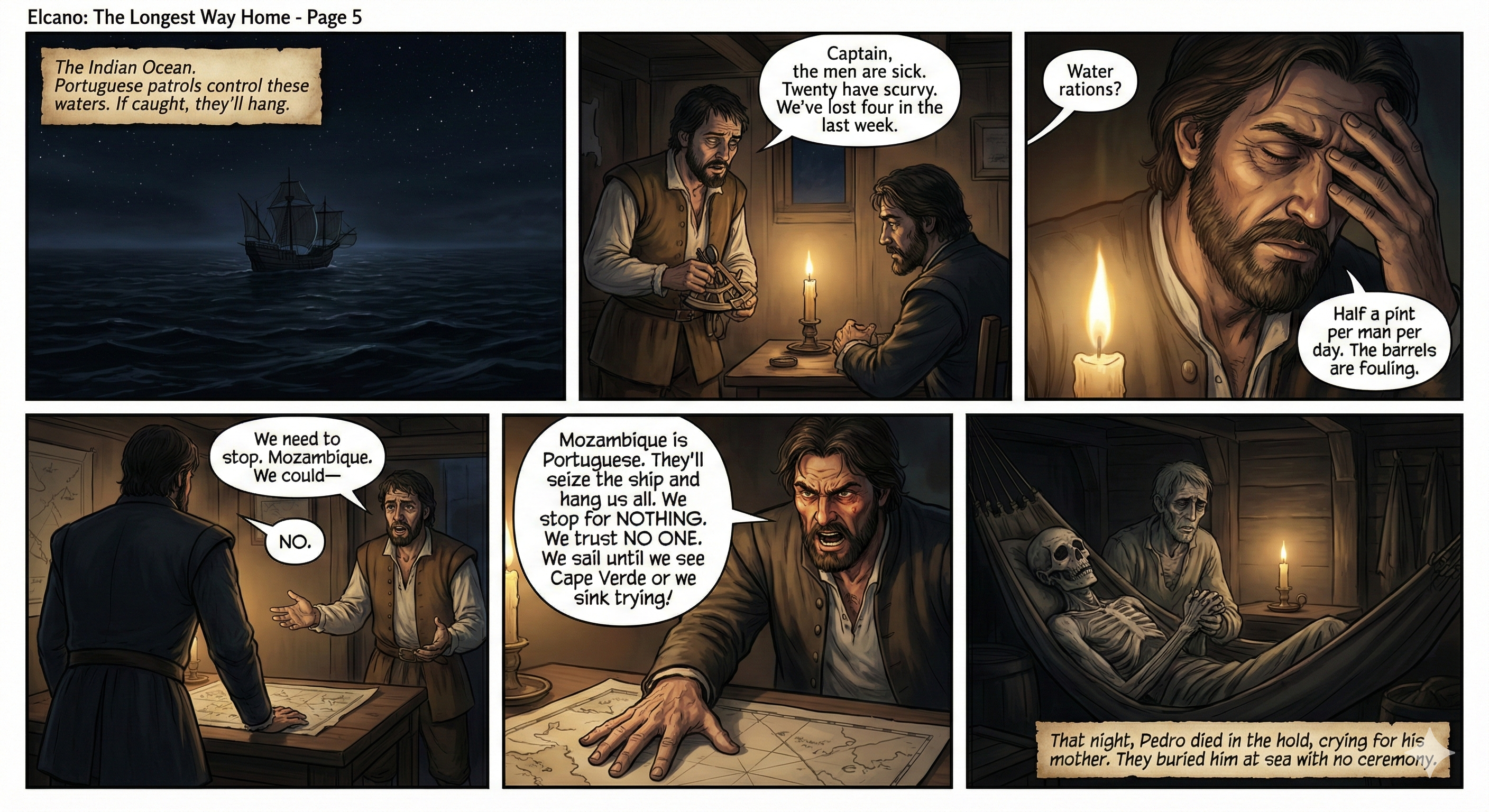

Portuguese patrols controlled these waters — if they were caught, they’d be hanged as trespassers in Portugal’s trading empire. Elcano ordered the ship silent at night, no lights, hugging distant shores they couldn’t name.

“Captain, the men are sick.” Francisco Albo, the pilot, looked exhausted. “Twenty have scurvy. We’ve lost four in the last week.” Become a member

Elcano had seen scurvy before — the bleeding gums, the loosening teeth, the terrible lethargy as men’s bodies simply gave up. They had no fresh food, only cloves and rice and the leathery remains of their supplies.

“Water rations?” he asked.

“Half a pint per man per day. The barrels are fouling.”

Elcano closed his eyes. Half a pint. In tropical heat. Sailing thousands of miles with men dying of thirst while surrounded by an ocean they couldn’t drink.

“We need to stop,” Albo said. “Mozambique. We could — “

“No.” Elcano’s voice was iron. “Mozambique is Portuguese. They’ll seize the ship and hang us all. We keep sailing.”

“But the men — “

“The men will die faster in a Portuguese prison!” Elcano slammed his hand on the chart. “We stop for nothing. We trust no one. We sail until we see Cape Verde or we sink trying.”

That night, a sailor named Pedro died in the hold, crying for his mother. They buried him at sea with no ceremony. There was no time. There was never time.

Part VI: The Cape of Storms

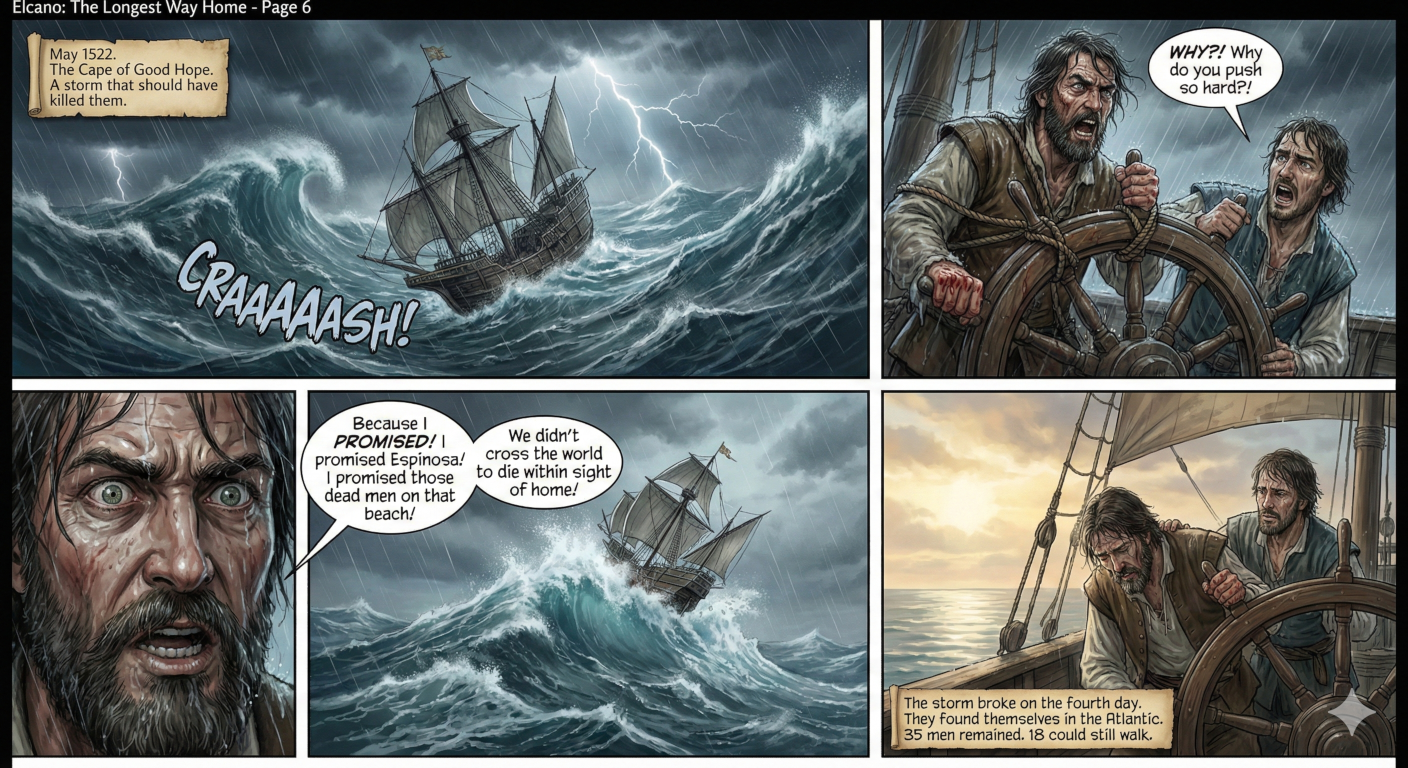

May 1522. The Cape of Good Hope.

They rounded it in a storm that should have killed them — waves like mountains, wind that tore at the rigging like claws. The Victoria was barely seaworthy, her hull leaking, her crew down to thirty-five men, most too weak to work.

Elcano lashed himself to the wheel for three days, refusing sleep, his hands bleeding on the spokes. Antonio Pigafetta held him steady when exhaustion made him sway.

“Why?” the Venetian shouted over the gale. “Why do you push so hard?”

Elcano’s eyes were mad, burning. “Because I promised! I promised Espinosa! I promised those dead men on that beach! We didn’t cross the world to die within sight of home!”

“You’re killing yourself!”

“Then I’ll die at the wheel, but this ship gets to Spain!”

The storm broke on the fourth day. They found themselves in the Atlantic, that familiar ocean they’d left nearly three years before. But they were skeletons now, a ghost ship with phantom crew.

Eighteen men could still walk. Thirteen could work. The rest lay in the hold, too weak to rise.

“We need water,” Albo said. “Food. Anything. Cape Verde is ahead — Portuguese, but we’ll die without stopping.”

Elcano stared at the horizon. The choice was impossible. Stop and risk capture. Sail on and watch his men die.

“We stop,” he said finally. “But we tell them we’re coming from America. We’re storm-damaged, need supplies. No one mentions the Pacific. No one mentions Magellan. Understood?”

Part VII: The Cape Verde Gambit

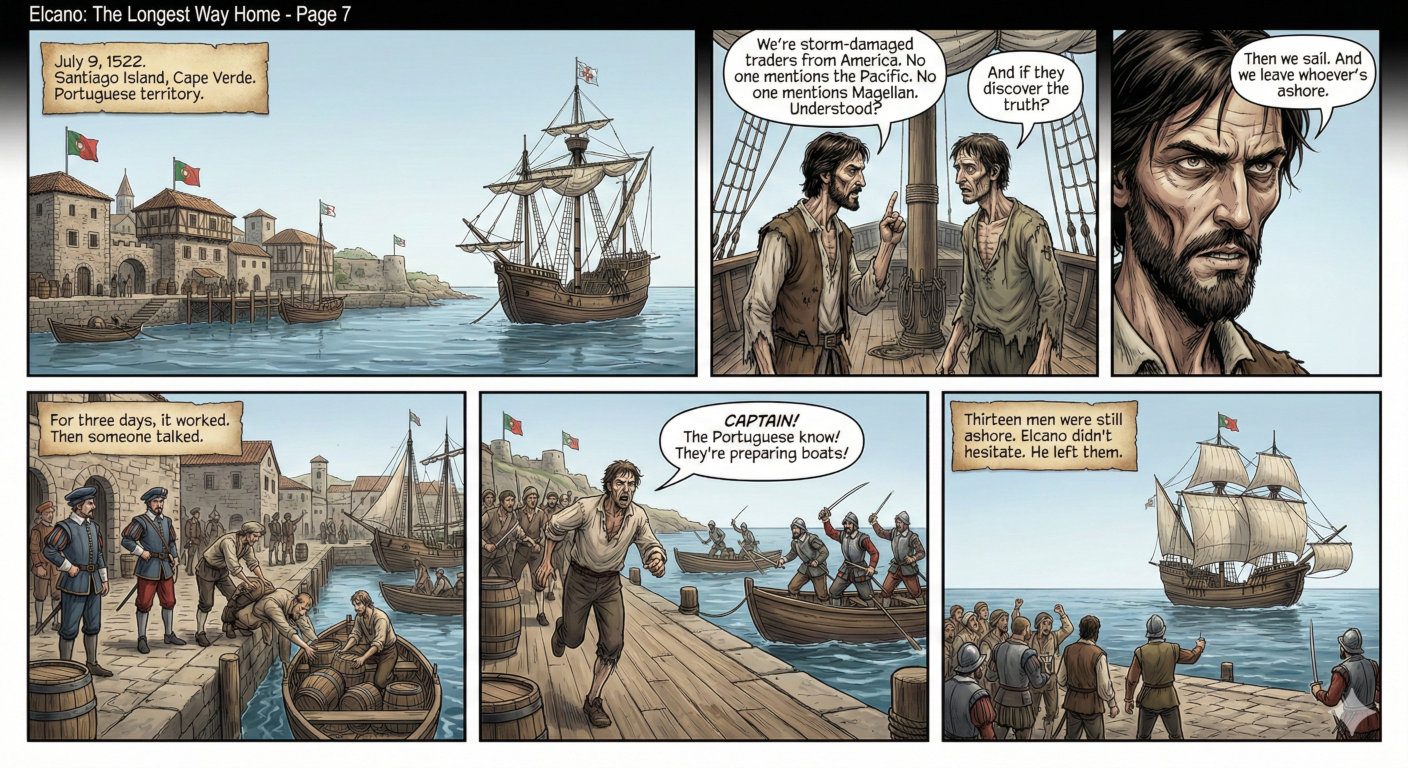

July 9th, 1522. Santiago Island, Cape Verde.

They traded cloves for rice and water, careful, paranoid. The Portuguese were suspicious but greedy for the spices. For three days, it worked.

Then someone talked.

“Captain!” The shout came from the dock. “The Portuguese know! They’re preparing boats!”

Elcano didn’t hesitate. “Cut the shore lines! Leave the landing party! Sail NOW!”

Thirteen men were still on the island, gathering supplies. They watched in horror as the Victoria spread her sails and fled, abandoning them to Portuguese imprisonment.

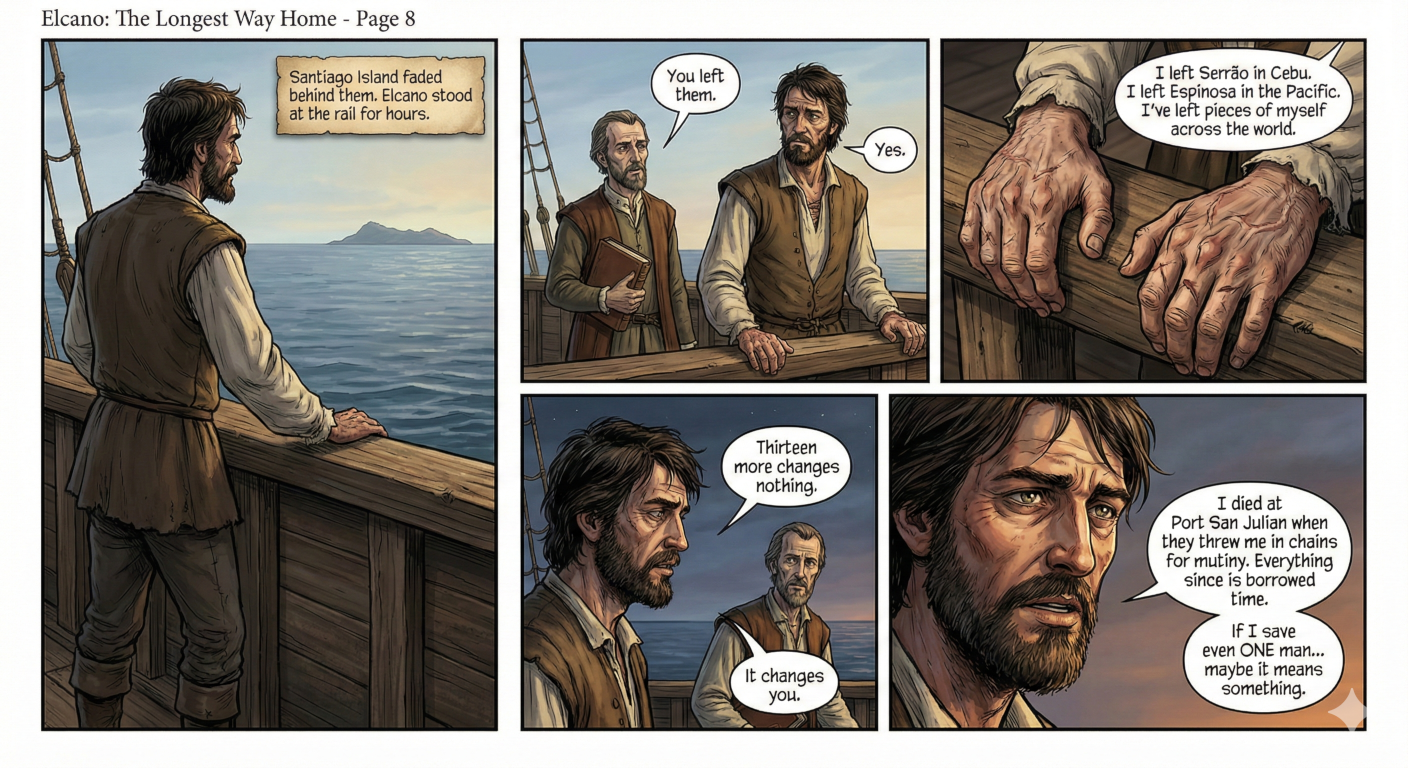

Pigafetta found Elcano at the rail, watching the island recede.

“You left them,” the Venetian said, and there was no judgment in his voice, only acknowledgment.

“Yes.” Elcano’s face was carved from granite. “I left Serrão in Cebu. I left Espinosa in the Pacific. I’ve left pieces of myself across the world. Thirteen more changes nothing.”

“It changes you.”

Elcano turned to him, and Pigafetta saw something broken behind the Basque’s eyes. “I died at Port San Julian when they threw me in chains for mutiny. Everything since is borrowed time. If I get this ship to Spain, if I save even one man, then maybe — maybe — it means something.”

“What does it mean?”

“That we were here. That we did the impossible. That we sailed around the world.”

Part VIII: Home

September 6th, 1522. Sanlúcar de Barrameda.

Eighteen men, more dead than alive, sailed the Victoria into Spanish waters. They’d left with 237 souls on five ships. They returned with eighteen on one battered caravel.

Elcano stood at the prow, barely able to stand. His body was wasted to bone, his hair prematurely white, his eyes haunted. But they’d done it. God in heaven, they’d actually done it.

“Antonio,” he said to Pigafetta, “write down their names. Every man who made it. So the world remembers who they were.”

The Venetian wept openly as he wrote: Juan Sebastián Elcano, Francisco Albo, Miguel de Rodas, Antonio Lombardo, Juan de Acurio… eighteen names. Eighteen miracles.

September 8th, they reached Seville. The city erupted. Church bells rang. People lined the streets, weeping, crossing themselves. These skeletons in rags were legend made flesh — they’d circumnavigated the globe, proven the world round, opened routes to unimaginable wealth.

King Charles V summoned Elcano to Valladolid. The Basque navigator knelt before his monarch, barely able to speak.

“Rise, Captain Elcano,” the king said. “What you’ve accomplished exceeds all human achievement. What do you desire as reward?”

Elcano thought of Magellan, of Serrão screaming on that beach, of Espinosa sailing into oblivion, of eighty men left behind across the world. Of three years that had aged him thirty.

“A coat of arms, Majesty,” he said quietly. “With the world upon it, and the words: Primus circumdedisti me. You first circumnavigated me.”

The king granted it. But Elcano knew the truth. The world hadn’t been conquered. It had conquered them. Broken them. Devoured them piece by piece until only eighteen remained to tell the tale.

That night, alone in his quarters, Juan Sebastián Elcano — mutineer, captain, survivor — finally let himself break. He wept for the dead, for the living, for the impossible weight of being the man who brought them home.

He’d sailed around the world.

And it had cost him everything.

Epilogue:

Elcano died five years later on another voyage across the Pacific, his body committed to the same ocean that had made him legendary. But on that September day in 1522, eighteen men proved that the world was one, that the impossible was merely difficult, and that the human spirit — stubborn, cruel, magnificent — could endure even the longest way home.

Primus circumdedisti me.

You first circumnavigated me.

The world remembers.