Behind the Legend of Magellan

Chapter 1: The Bitter Taste of Rejection

Setting: Lisbon, Portugal — Late 1515 to Early 1516

Ferdinand Magellan, scarred veteran of Portuguese expeditions to the East Indies, returns to the court of King Manuel I with a revolutionary proposal. Having witnessed the wealth of the Spice Islands firsthand, he believes he can reach them by sailing west around the Americas, potentially giving Portugal an alternative route to their eastern empire.

The morning mist clung to the Tagus River like the ghosts of dead sailors as Ferdinand Magellan limped through the cobblestone streets of Lisbon. Each step sent fire through his wounded leg, a permanent reminder of the Moorish lance that had nearly ended his life at Azamor. But the physical pain was nothing compared to the burning humiliation that had been eating at his soul for months.

He clutched the leather satchel containing his most precious possession — detailed charts of the Spice Islands, drawn from his own observations during seven brutal years in Portuguese Asia. Those maps represented more than geography; they were the key to unimaginable wealth, routes to islands where nutmeg and cloves grew like common weeds, where a single ship’s cargo could make a man richer than most European nobles.

As Magellan approached the imposing walls of the Royal Palace, he rehearsed his proposal one final time. The western route. It was audacious, perhaps impossible, but theoretically sound. If the Americas could be circumnavigated from the south, if there truly was a passage to the western ocean, then Portugal could reach their Asian empire by sailing west instead of east. They could bypass the treacherous Cape of Good Hope, avoid the monsoons of the Indian Ocean, and establish a second lifeline to their precious colonies.

The palace guards recognized him — who could forget that distinctive limp? — but their respectful nods felt more like mockery now. Once, Ferdinand Magellan had been a hero, a man who had fought for Portugal’s glory in the farthest corners of the world. Now he was just another aging veteran with grandiose dreams and an empty purse.

Inside the opulent halls, courtiers whispered behind jeweled hands. Their silks rustled like serpents as they turned to watch him pass. Magellan held his head high, but he could feel their judgment like arrows in his back. He knew what they were thinking: there goes the crippled dreamer, the man who thinks he can sail to Asia by going the wrong direction.

The antechamber to King Manuel I’s private audience room was a monument to Portuguese maritime supremacy. Tapestries depicted Vasco da Gama’s triumphant return from India, Pedro Cabral’s discovery of Brazil, and Alfonso de Albuquerque’s conquest of Malacca. Each thread seemed to mock Magellan’s current circumstances. He had been there, fought in those very battles that now decorated the walls, yet his name appeared on none of the golden plaques.

“His Majesty will see you now,” announced the royal secretary, a thin man whose disdain was barely concealed behind court protocol.

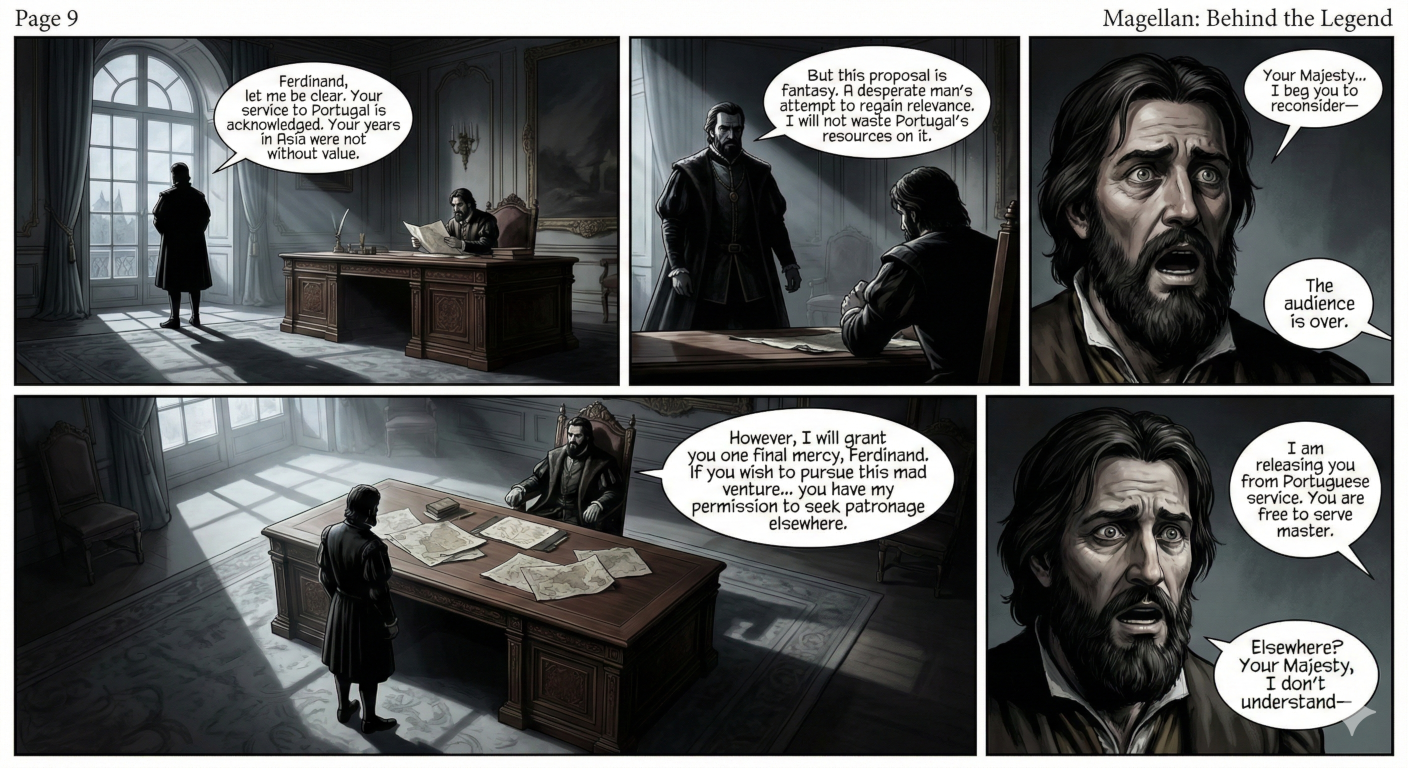

King Manuel I sat behind an enormous desk of Brazilian rosewood, its surface covered with maps, trade reports, and correspondence from across the Portuguese Empire. At forty-six, the king was still handsome, his beard meticulously groomed, his dark eyes sharp with intelligence. But there was something cold in his gaze as he looked up at Magellan, something that suggested this audience was merely a formality, a final gesture before closing a troublesome chapter.

“Ferdinand,” the king said, not bothering to use his proper title. “I understand you have another petition for me.”

Magellan bowed as low as his injured leg would allow. “Your Majesty, I come not as a supplicant, but as a loyal servant who has discovered an opportunity that could secure Portugal’s dominance for centuries to come.”

Manuel leaned back in his chair, his fingers drumming against the rosewood. “Speak.”

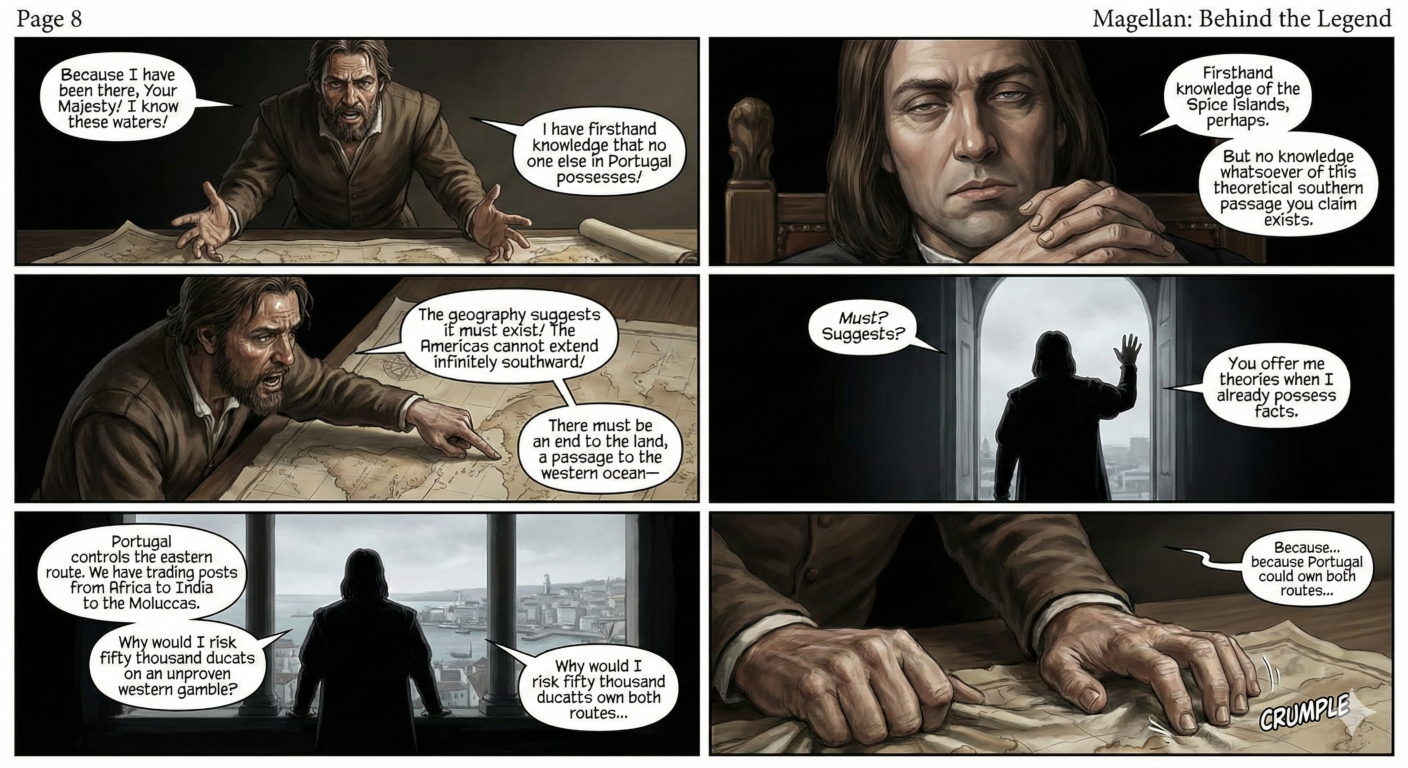

With trembling hands, Magellan unrolled his charts across the royal desk. The king’s eyes widened slightly at the detail and precision of the maps — these were not the crude sketches of an amateur, but the professional work of a seasoned navigator who had sailed those waters himself.

“Your Majesty, behold the Spice Islands — Ternate, Tidore, the Bandas. I have walked their shores, breathed their perfumed air, seen their treasures with my own eyes.” Magellan’s voice grew stronger as he warmed to his subject. “But observe this — “ he traced a finger along the western edge of his map, where the Americas appeared as a barrier. “What if this land mass can be circumnavigated? What if there is a passage here, in the south, that leads to a western ocean?”

Manuel’s expression remained neutral, but Magellan caught a flicker of interest in the royal eyes.

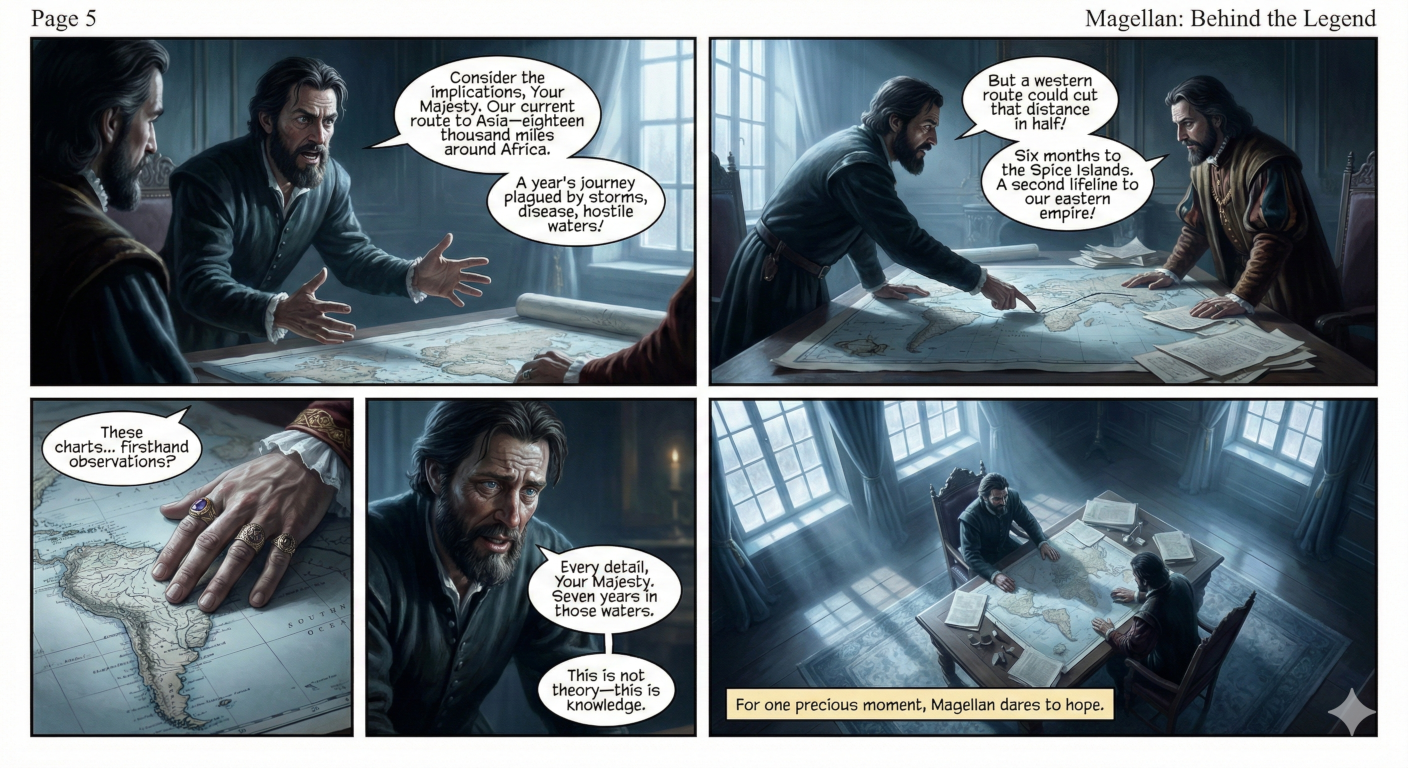

“Consider the implications, Your Majesty. Our current route to Asia is eighteen thousand miles around Africa — a year’s journey plagued by storms, disease, and hostile waters. But if my calculations are correct, a western route could cut that distance in half. We could reach the Spice Islands in six months, establish a second lifeline to our eastern empire, and leave our competitors floundering around the Cape of Good Hope like blind men.”

The king studied the charts in silence, his trained eye taking in the coastal details, the wind patterns, the notations that could only come from firsthand experience. Magellan held his breath, daring to hope that perhaps, finally, his vision would be recognized.

“And you believe this southern passage exists?” Manuel asked finally.

“I do, Your Majesty. The Spanish have explored the northern coasts of the New World, but the southern regions remain largely unknown. If we could mount an expedition — five ships, perhaps, with experienced crews — “

“At what cost?” The king’s voice cut through Magellan’s enthusiasm like a blade.

Magellan hesitated. He had hoped to build the king’s excitement before discussing practicalities. “Such an expedition would require significant investment, Your Majesty. Perhaps fifty thousand ducats — “

Manuel’s laugh was sharp and mirthless. “Fifty thousand ducats? To chase shadows across unknown seas based on the theories of a man who cannot even secure a modest increase to his own pension?”

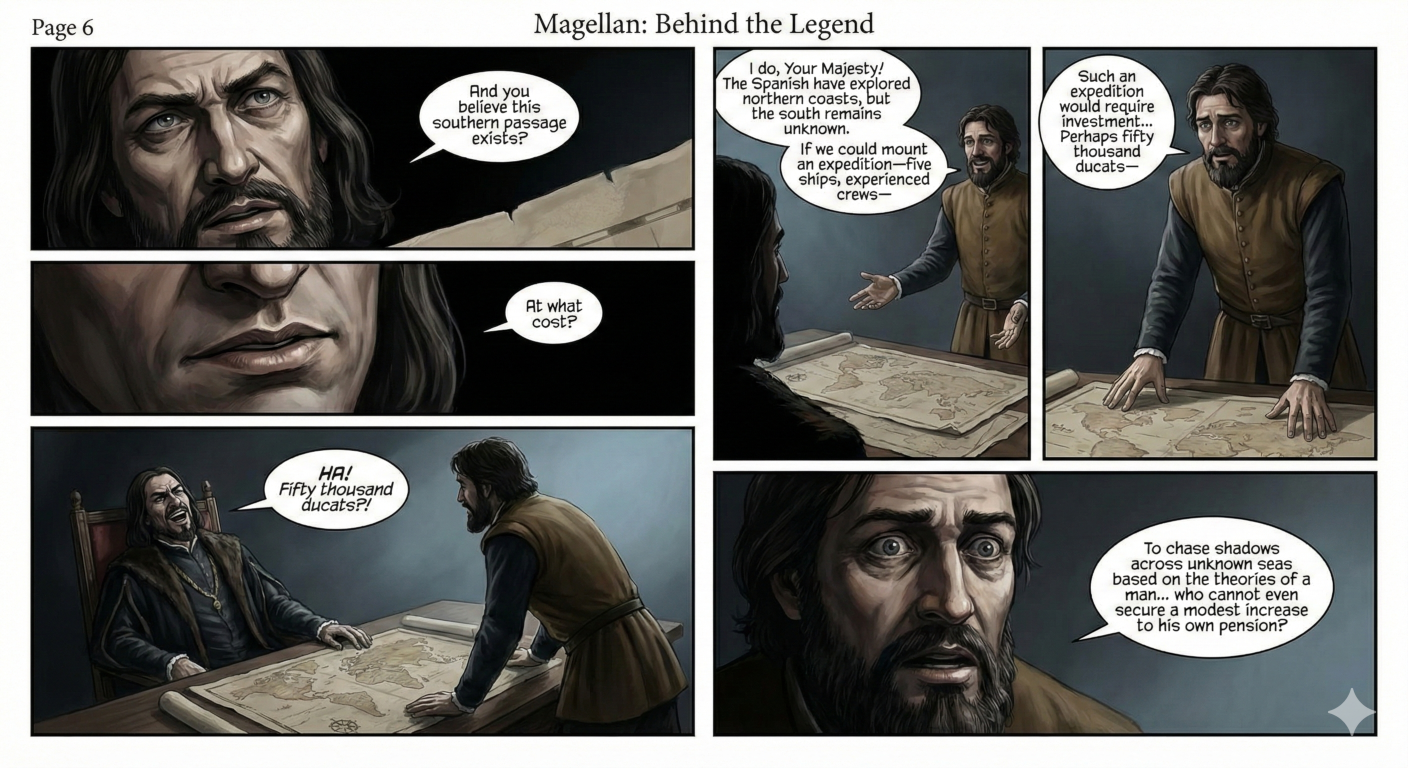

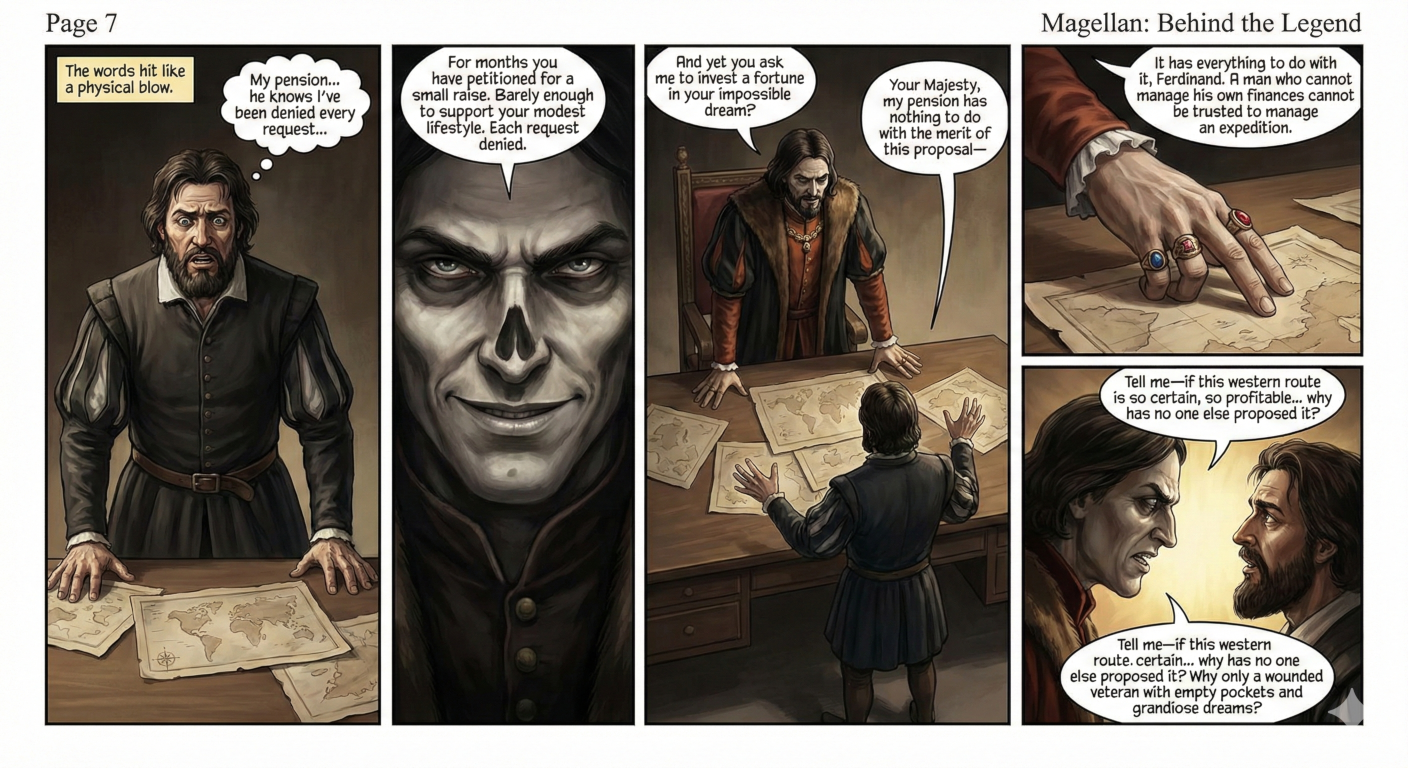

The words hit Magellan like a physical blow. For months, he had been petitioning for a small raise in his military pension — barely enough to support his modest lifestyle, let alone his growing family. Each request had been denied with bureaucratic efficiency, as if his years of service meant nothing.

“Your Majesty, my pension has nothing to do with the merit of this proposal — “

“Does it not?” Manuel stood, his height and regal bearing making Magellan feel suddenly small. “You come before me asking for enormous sums to fund your western fantasy, yet you cannot demonstrate that your ideas have any value. If your strategic thinking was sound, would you not have prospered in our eastern ventures? If your navigation skills were exceptional, would you not hold a position of importance in our fleet?”

Magellan felt heat rising in his cheeks. “Your Majesty, I have served Portugal faithfully for fifteen years. I fought at Cannanore, helped establish our factory at Cochin, participated in the conquest of Malacca — “

“And yet you limp,” Manuel interrupted coldly. “You limp because you were careless enough to let a Moorish lance find its mark at Azamor. You limp because you lack the skill to avoid injury in battle. Why should I trust such a man to navigate uncharted waters?”

The cruelty of the words took Magellan’s breath away. His wound had been earned in Portuguese service, fighting Portuguese battles, expanding Portuguese territory. To have it thrown back at him as evidence of weakness was almost unbearable.

But worse was to come.

“Moreover,” the king continued, beginning to pace behind his desk, “your proposal demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of our strategic position. Portugal looks east, Magellan. East to India, to China, to the riches we have already secured through blood and gold. We have built an empire stretching from Brazil to Macau, a trading network that spans half the world. Why would we jeopardize this magnificent achievement to chase uncertainties in the west?”

“Because the east is vulnerable, Your Majesty!” Magellan’s composure finally cracked. “Our Indian fleet faces constant storms, our factories are under perpetual threat from local rulers, our supply lines stretch across eighteen thousand miles of hostile water. One major disaster, one successful enemy campaign, and our entire eastern empire could collapse. A western route would provide security, redundancy — “

“It would provide competition with ourselves!” Manuel slammed his hand on the desk, causing the charts to jump. “Think, man! If we establish a western route to the Spice Islands, what prevents the Spanish from following in our wake? What stops them from claiming those islands lie on their side of the papal line? Your western passage would not secure our eastern empire — it would give it away to our enemies!”

The argument hit Magellan like a revelation. In his enthusiasm for the navigational challenge, he had not fully considered the political implications. The Treaty of Tordesillas had divided the world between Spain and Portugal along a north-south line, but that division had been calculated based on eastward navigation. If the Spice Islands could be reached by sailing west, their ownership under the treaty became ambiguous at best.

But even as he recognized the validity of the king’s concern, Magellan’s strategic mind began working on solutions. “Your Majesty, we could claim the western route as Portuguese territory, establish fortified bases along the way — “

“With what ships? What men? What gold?” Manuel’s voice rose with each question. “Every vessel in our fleet is already committed to defending our existing territories. Every soldier is already fighting our existing wars. Every ducat in our treasury is already spoken for by our existing commitments. You ask me to weaken our established empire to chase your western fantasy, and for what? The possibility — the mere possibility — that you might find a passage that might lead to islands we already control by a route we already know?”

Magellan opened his mouth to respond, but Manuel was not finished.

“And what of the risks? You speak glibly of circumnavigating the Americas, as if it were a pleasant cruise along the Portuguese coast. Have you forgotten the storms that destroyed Cabral’s fleet? The diseases that killed half of da Gama’s men? The hostile natives who have massacred dozens of our explorers? You propose to sail into completely unknown waters, around the bottom of a continent whose size we do not know, across an ocean whose existence we cannot confirm, and you expect me to fund this madness with the treasury of Portugal?”

The king’s words echoed in the vast chamber, each syllable a nail in the coffin of Magellan’s dreams. But still, he could not give up. Too much depended on this moment — his future, his family’s security, his place in history.

“Your Majesty,” he said quietly, “I understand your concerns. But consider this — every great Portuguese achievement began as an impossible dream. Prince Henry’s captains said the African coast could not be rounded. da Gama’s advisors said the Indian Ocean was a myth. Cabral’s critics said the western ocean held only monsters. Yet we proved them all wrong, and Portugal became the greatest maritime power in the world because we dared to attempt the impossible.”

For a moment, Manuel’s expression softened slightly. Magellan pressed his advantage.

“I do not ask you to abandon our eastern empire, Your Majesty. I ask you to strengthen it. Give me five ships — old vessels that would be decommissioned anyway. Give me volunteers — men seeking adventure rather than pressed sailors. Give me a modest budget — a fraction of what we spend maintaining a single Indian factory. If I succeed, Portugal gains an alternate route to our most valuable territories. If I fail…” Magellan spread his hands. “You lose only what you were prepared to discard.”

The king considered this for a long moment, his dark eyes studying Magellan’s scarred face. Finally, he spoke.

“You speak of modest budgets and old ships, but we both know that is false economy. A voyage of this magnitude requires the finest vessels, the most experienced crews, the best supplies. Half-measures would only ensure disaster. And even if you succeeded, even if you found your impossible passage, what then? Do you think the Spanish would simply watch as we establish a western route to the Indies? Do you think they would not follow, would not claim their own share of the profits?”

Manuel walked to the great window overlooking the Tagus, where Portuguese caravels bobbed at anchor like sleeping seabirds. “Portugal’s strength lies not in grand gestures or impossible quests, Magellan. It lies in methodical expansion, careful consolidation, the patient accumulation of practical advantages. We have built our empire step by step, harbor by harbor, trading post by trading post. We did not achieve our current position by gambling everything on the dreams of wounded veterans.”

The dismissal in the king’s voice was unmistakable, but Magellan made one final attempt.

“Your Majesty, I have served Portugal faithfully for fifteen years. I have bled for this crown, fought for this realm, expanded this empire. Surely that service earns me the right to be heard, to have my ideas given serious consideration?”

Manuel turned from the window, and Magellan was shocked by the coldness in his eyes.

“Your service, Ferdinand, has been adequate. Nothing more. You have done your duty as thousands of other men have done theirs. You have earned your pension — modest though it may be — and the right to live quietly in retirement. But you have not earned the right to dictate national strategy or to gamble with the royal treasury.”

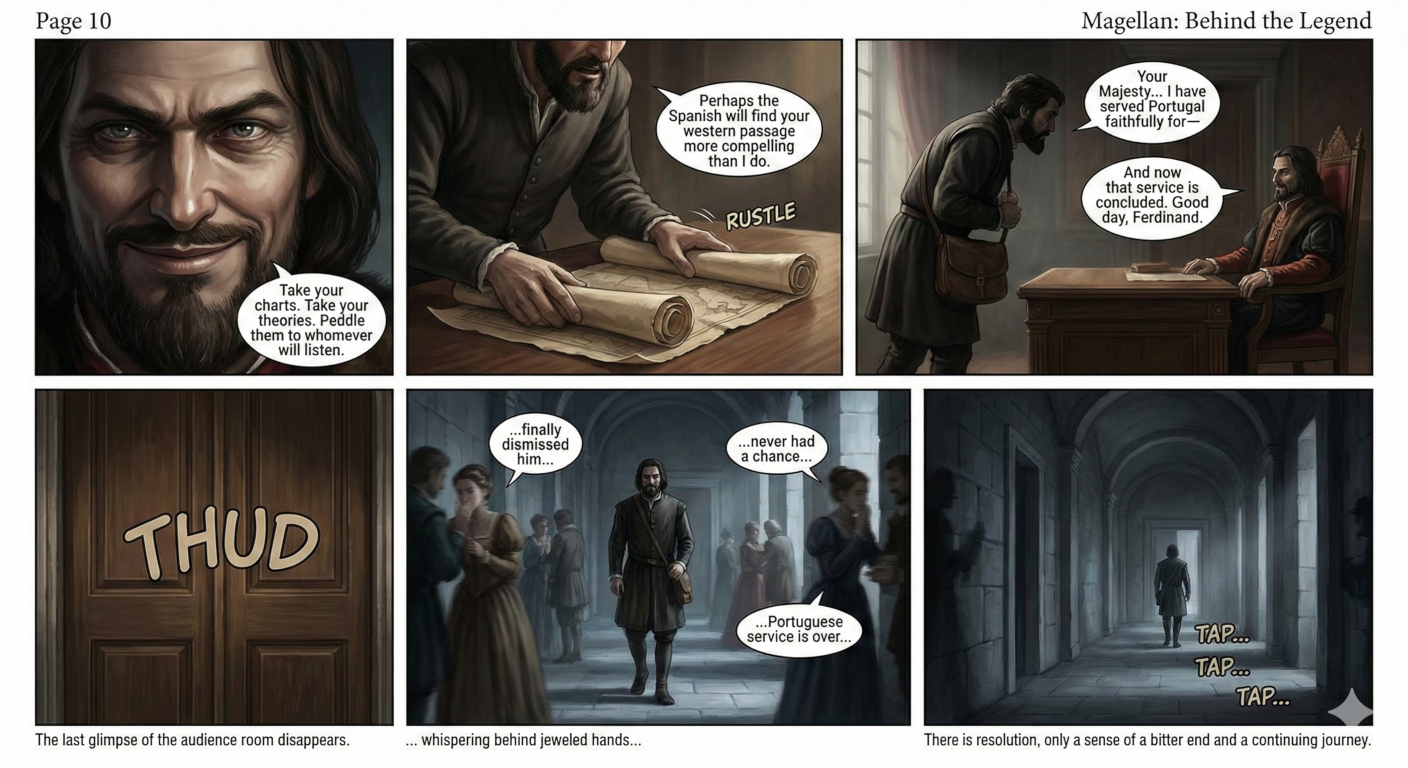

The king returned to his desk and began rolling up Magellan’s charts. “Your western route is an interesting theoretical exercise, but it has no practical application to Portugal’s current needs. We will continue to focus our resources on consolidating and defending our existing territories.”

Magellan watched his carefully drawn maps disappear into their leather case, feeling as if his future was being rolled up with them. But he had one last card to play — a desperate gambit that might salvage something from this disaster.

“Your Majesty,” he said, his voice barely above a whisper, “if Portugal cannot use my skills, perhaps… perhaps you would grant me permission to seek service elsewhere?”

The words hung in the air like incense, heavy with implications. Manuel’s hands stilled on the charts, and when he looked up, there was something dangerous in his expression.

“Elsewhere, Ferdinand? Where exactly did you have in mind?”

Magellan’s throat felt dry as sand. He had not meant to be so direct, but desperation had pushed him beyond diplomatic caution. “There are other maritime powers, Your Majesty. Other crowns that might value experience in eastern navigation.”

“Ah.” Manuel’s smile was thin and cold. “Now we come to the truth of it. This is not about serving Portugal, is it, Ferdinand? This is about finding someone — anyone — who will fund your western obsession. Tell me, have you already made inquiries? Have you already approached our enemies with offers to betray Portuguese secrets?”

“Never, Your Majesty!” Magellan’s protest was immediate and heartfelt. “I have never betrayed Portugal’s trust, would never — “

“But you would consider it, wouldn’t you?” Manuel stood slowly, his height and authority filling the room. “You would take your knowledge of our eastern routes, our trading practices, our military strengths and weaknesses, and you would sell them to the highest bidder. All in service of your grand western dream.”

“I would never compromise Portugal’s interests, Your Majesty. But if my own country cannot find use for my skills — “

“Cannot find use?” Manuel’s voice rose to a roar. “We gave you fifteen years of employment! We paid for your passage to India, your supplies, your weapons, your medical care when you were wounded! We granted you pension and privileges, rank and recognition! And now, because we refuse to fund your impossible fantasy, you threaten to take our secrets to our enemies?”

Magellan realized he had pushed too far, revealed too much of his desperation. “Your Majesty, I meant no threat. I merely sought to understand whether my services might be released if they are no longer needed here.”

Manuel studied him for a long moment, and when he spoke, his voice was deadly quiet.

“Very well, Ferdinand. Since you seem so eager to explore other opportunities, I hereby grant your request. You are released from Portuguese service. You may seek employment wherever your conscience allows. But understand this — if you betray Portuguese interests, if you reveal Portuguese secrets, if you take actions that harm this realm in any way, I will hunt you to the ends of the earth. I will see you hanged as a traitor, and your family will bear the shame of your treachery for generations.”

The threat was delivered with such casual certainty that Magellan felt ice in his veins. He had pushed for this moment, had asked for exactly what the king was now granting, but the reality of it was terrifying. To be released from Portuguese service was to lose his identity, his purpose, his place in the world. He would become a man without a country, a navigator without a fleet, a dreamer without a patron.

“Your Majesty,” he began, but Manuel raised a hand to silence him.

“The audience is concluded, Ferdinand. I wish you good fortune in your future endeavors. May you find someone willing to gamble on your western passage. Portugal will watch your progress with… interest.”

Magellan bowed deeply, his wounded leg nearly buckling under the weight of his humiliation. As he gathered his charts and turned toward the door, Manuel’s voice followed him.

“Oh, and Ferdinand? When you speak to your new patrons about the Spice Islands, remember that they belong to Portugal. By right of discovery, by right of conquest, by papal decree and royal charter. No western route will change that fact. No foreign expedition will alter our legal claim. The man who attempts to steal our eastern empire will find himself at war with the Crown of Portugal.”

The warning was unmistakable, and Magellan felt it like a weight on his shoulders as he limped through the palace corridors. Courtiers who had barely acknowledged him before now watched with undisguised curiosity. Word traveled fast in royal circles, and by evening, all of Lisbon would know that Ferdinand Magellan had been cast out of Portuguese service.

Outside the palace, the morning mist had burned away, leaving the city bright and bustling under the autumn sun. Merchants hawked their wares, sailors prepared their ships, and life continued with the same rhythm it had maintained for centuries. But for Magellan, everything had changed. He was no longer a Portuguese officer, no longer a servant of the crown that had defined his adult life. He was just another aging veteran with impossible dreams and an uncertain future.

As he walked slowly through the familiar streets, his mind raced with possibilities and fears. Where could he go? Who would listen to his proposals? How could he support his family while pursuing his western obsession? The questions multiplied with each step, but beneath them all lay a growing certainty: if Portugal would not recognize his worth, he would find someone who would.

The harbor stretched before him, filled with Portuguese vessels preparing for their eternal journey east. But Magellan’s eyes looked west, toward the unknown lands where his destiny lay waiting. King Manuel had called his western route an impossible fantasy, but Magellan knew better. Somewhere beyond the sunset, past the edge of every known map, lay a passage that would change the world. He would find it, with or without Portugal’s blessing.

The salt wind carried the scent of adventure and the promise of redemption. Ferdinand Magellan, no longer a Portuguese navigator, limped toward his uncertain future with his charts tucked under his arm and revolution burning in his heart.

Chapter 2: The Desperate Gambit

Setting: Journey from Lisbon to Seville, Spain — 1516–1517

Stripped of his Portuguese identity and purpose, Magellan embarks on a dangerous journey to Spain. He must reinvent himself as a Spanish patriot while secretly nursing his desire for revenge against Manuel I. The transformation from Fernão de Magalhães to Fernando de Magallanes represents both opportunity and betrayal.

The October wind cut through Ferdinand Magellan’s cloak like a blade as he stood on the deck of the Portuguese merchant vessel Santa Maria da Esperança, watching the familiar coastline of his homeland disappear into the morning haze. Each league that passed beneath the ship’s hull carried him further from everything he had ever known — his country, his identity, his past. At thirty-six years old, he was starting over with nothing but his charts, his dreams, and a burning desire for vindication.

Beside him at the rail stood Rui Faleiro, a thin, intense man whose brilliant mind had been equally rejected by Portuguese academia. Faleiro was a cosmographer of extraordinary skill, a mathematician who could calculate longitude with unprecedented accuracy, and — like Magellan — a man whose genius had been dismissed by those too conservative to recognize its value.

“Fernão,” Faleiro said quietly, using Magellan’s Portuguese name perhaps for the last time, “are you certain about this path? Once we set foot in Spain, there will be no turning back. Manuel’s spies will be watching, waiting for any sign of treachery.”

Magellan’s hands tightened on the ship’s rail. The name Fernão de Magalhães felt like a coat that no longer fit, heavy with the weight of rejection and humiliation. “That man died in Manuel’s throne room, Rui. The person who disembarks in Seville will be Fernando de Magallanes, servant of the Spanish crown.”

“Can you truly transform yourself so completely? Abandon everything that made you who you are?”

Magellan turned to face his friend, and Faleiro was struck by the cold determination in those dark eyes. “What made me who I was? Fifteen years of faithful service, rewarded with contempt. Wounds earned in Portuguese battles, mocked as signs of weakness. Knowledge gained at tremendous cost, dismissed as the fantasies of a crippled dreamer.” He shook his head bitterly. “If that is who I was, then I am glad to be rid of him.”

The voyage to Seville took twelve days, but for Magellan, it felt like a journey between worlds. Each night, he practiced speaking Spanish, slowly erasing the Portuguese accent that had marked him since childhood. He studied Spanish customs, Spanish politics, Spanish ways of thinking. Most importantly, he worked with Faleiro to refine their proposal, adapting it to appeal to Spanish interests rather than Portuguese ones.

“The key,” Faleiro explained as they huddled over their charts in the ship’s cramped cabin, “is to frame this not as a challenge to Portugal, but as an opportunity for Spain. We must convince them that the western route serves their interests without threatening their neighbors.”

Magellan laughed bitterly. “Without threatening their neighbors? Rui, this entire enterprise is designed to break Portugal’s monopoly on the spice trade. How can we disguise that fact?”

“By emphasizing the legal aspects,” Faleiro replied, his scholarly mind already working through the complexities. “The Treaty of Tordesillas divided the world along a north-south line, but it said nothing about western approaches to eastern territories. If the Spice Islands lie on the Spanish side of that line when approached from the west, then Spain has every right to claim them.”

“And if they lie on the Portuguese side?”

Faleiro’s smile was sharp. “Then we discover that fact only after we have already established a Spanish presence there. Possession, as they say, is nine-tenths of the law.”

As the Spanish coast came into view, Magellan felt his stomach tighten with a mixture of excitement and terror. Everything he had worked for, everything he had sacrificed, came down to this moment. Either Spain would embrace his vision, or he would be left with nothing — no country, no patron, no future.

The port of Seville was a marvel of commerce and ambition. Ships from across the Spanish Empire crowded the harbor — galleons loaded with American silver, caravels carrying exotic goods from the Indies, warships bristling with cannons. The wealth of the New World flowed through this port like a golden river, and Magellan could see opportunity in every sail.

“Look at it, Rui,” he said as they disembarked on October 20, 1517. “Spain has conquered half the world in just twenty-five years. They have gold, silver, territory, ambition — everything except direct access to the Spice Islands. We can give them that.”

Their first weeks in Seville were a humbling experience. Without royal patronage or official introduction, they were just two more foreign opportunists seeking Spanish gold. They took modest lodgings in the Santa Cruz district, spending their dwindling funds carefully while seeking connections to the Spanish court.

Magellan’s transformation was not merely linguistic but psychological. He had to learn to think like a Spaniard, to see the world through Spanish eyes. Portugal’s eastern empire, which he had spent his life building and defending, now became the enemy’s monopoly that needed to be broken. The Spice Islands, which he had helped secure for his homeland, now became territories that rightfully belonged to Spain.

The moral weight of this transformation was crushing. Late at night, alone in his sparse room, Magellan would lie awake staring at the ceiling, wondering if he had become the traitor that Manuel had accused him of being. Was he serving a greater good by bringing Spanish competition to Portuguese trade routes, or was he simply a bitter man seeking revenge against those who had rejected him?

The answer came to him gradually, through conversations with Spanish merchants and officials who painted a picture of Portugal’s eastern empire as a corrupt monopoly that artificially inflated spice prices throughout Europe. These men spoke of Portuguese factors who grew rich while European consumers paid exorbitant prices for nutmeg and cloves. They described a trading system that benefited only a small Portuguese elite while leaving Spanish merchants excluded from the most profitable commerce in the world.

“Don Portugal thinks he can control the spice trade forever,” complained Diego Barbosa, a Spanish merchant who had become one of Magellan’s closest allies. “But why should one nation hold monopoly over goods that God intended for all humanity? The Spice Islands produce enough nutmeg and cloves to supply every kitchen in Europe, yet we pay through the nose for a few ounces because the Portuguese control the only known route.”

These conversations helped Magellan rationalize his defection. He was not betraying Portugal — he was liberating Europe from Portuguese tyranny. He was not stealing Spanish secrets — he was sharing Portuguese knowledge for the benefit of all mankind. The western route would not destroy Portugal’s eastern empire — it would simply provide healthy competition that would benefit consumers throughout Christendom.

But rationalization could not entirely quiet the voice of conscience. When letters arrived from his wife Beatriz, still living in Portugal with their infant son, Magellan felt the full weight of his choices. His family was suffering financially — his Portuguese pension had been suspended following his defection, and Beatriz was forced to rely on the charity of relatives. His son would grow up knowing that his father had abandoned his homeland for foreign gold.

“I am doing this for them,” he told himself, but the words felt hollow. Was he really sacrificing his family’s present for their future, or was he simply using them as an excuse to pursue his obsession with the western route?

The breakthrough came in November 1517, when Magellan was introduced to Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, Bishop of Burgos and one of the most powerful men in the Spanish government. Fonseca controlled the Casa de Contratación, the royal agency that managed Spanish trade with the Americas, and his support would be crucial for any major expedition.

The bishop was a shrewd man in his sixties, with the soft hands of a churchman and the sharp eyes of a politician. He received Magellan in his private study, surrounded by maps, trade reports, and correspondence from across the Spanish Empire.

“So,” Fonseca said, settling back in his chair, “you are the Portuguese navigator who claims he can reach the Spice Islands by sailing west. Tell me, Señor Magallanes, why should Spain trust a man who has already betrayed one master?”

The question was direct and dangerous, but Magellan had prepared for it. “Your Excellency, I have not betrayed Portugal — Portugal betrayed me. I served faithfully for fifteen years, earned my wounds in Portuguese battles, expanded Portuguese territory at the cost of my own blood. When I brought them the opportunity to secure their eastern empire with a western route, they mocked my injuries and dismissed my knowledge. A man cannot betray a country that has already cast him out.”

Fonseca studied him carefully. “And yet you possess detailed knowledge of Portuguese trade routes, Portuguese military capabilities, Portuguese weaknesses. Knowledge that would be extremely valuable to Spain’s enemies.”

“I possess knowledge of the Spice Islands themselves, Your Excellency. I have walked their shores, negotiated with their rulers, mapped their harbors. That knowledge belongs not to Portugal but to whoever can use it most effectively. Portugal has proven they cannot — or will not — use it to benefit anyone beyond their own narrow interests.”

“And you believe Spain can?” Become a member

Magellan leaned forward, his voice growing passionate. “Your Excellency, Spain has accomplished miracles in the past quarter-century. You have conquered the Aztecs, subdued the Incas, established colonies from California to Chile. You have demonstrated that Spanish courage and Spanish enterprise can achieve what other nations only dream of. But you lack access to the most profitable trade in the world — the spice trade that makes Portugal rich while Spanish merchants are excluded.”

He pulled out his charts, spreading them across the bishop’s desk. “Here are the Spice Islands — Ternate, Tidore, Banda, Ambon. Islands so rich that a single ship’s cargo can buy a palace in Seville. Portugal reaches them by sailing eighteen thousand miles around Africa, a journey that takes a year and costs countless lives. But if there is a passage here — “ he pointed to the southern tip of the Americas “ — then Spain could reach these islands in six months, establish Spanish factories, and break Portugal’s monopoly forever.”

Fonseca examined the charts with growing interest. “And you believe this passage exists?”

“I believe it must exist, Your Excellency. The Americas cannot extend infinitely southward — there must be a point where they end, where the western ocean begins. Spanish explorers have already reached the western coast of the New World. The question is not whether a passage exists, but whether Spain has the courage to find it.”

The bishop smiled at the subtle challenge. “You think to goad us into funding your expedition by questioning Spanish courage? That is a dangerous game, Señor Magallanes.”

“I think to remind you of Spanish achievements, Your Excellency. Twenty-five years ago, Christopher Columbus convinced your Catholic Majesties to fund an expedition to reach the Indies by sailing west. Everyone said it was impossible — the ocean was too vast, the risks too great, the cost too high. But Spanish courage proved the skeptics wrong, and Spain gained an entire New World. Now I offer you the same opportunity — the chance to reach the Old World by a new route, to break the Portuguese monopoly, to establish Spanish dominance in the spice trade.”

Fonseca was quiet for a long moment, his fingers drumming on the desk. Finally, he spoke.

“The comparison to Columbus is apt, but perhaps not in the way you intend. Columbus promised to reach the Indies by sailing west, and he failed. He found continents instead of islands, savages instead of spice merchants, gold instead of pepper. His voyage was a magnificent failure that happened to discover something even more valuable than what he sought.”

“And you fear that my expedition might also fail in its stated purpose?”

“I fear that your expedition might succeed in its stated purpose,” Fonseca replied. “Columbus’s failure gave Spain exclusive access to the Americas. Your success would give Spain access to territories that Portugal already claims by right of prior discovery. The legal complications alone could trigger a war between the two crowns.”

Magellan had anticipated this objection. “Your Excellency, the legal situation is far from clear. The Treaty of Tordesillas established a line of demarcation in the Atlantic, but it said nothing about the Pacific. If the Spice Islands lie on the Spanish side of that line when approached from the west, then Spain has every right to claim them. We can only determine their true position by actually reaching them via the western route.”

“And if they lie on the Portuguese side?”

“Then we will have established Spain’s good faith in attempting to respect the treaty boundaries. No one can accuse us of territorial aggression if we discover the islands belong to Portugal only after we have already invested enormous resources in reaching them.”

Fonseca laughed despite himself. “You argue like a Jesuit, Señor Magallanes. But tell me honestly — do you truly believe the Spice Islands will prove to be on the Spanish side of the line?”

Magellan met his gaze directly. “Your Excellency, I believe the Spice Islands will prove to be wherever Spanish courage and Spanish enterprise can reach them. Geography is important, but possession is more important still.”

The bishop nodded slowly. “Now you speak like a true conquistador. Very well, Señor Magallanes, I am sufficiently intrigued to arrange an audience with His Majesty. But understand — King Charles is young, and he is surrounded by advisors who will scrutinize every aspect of your proposal. You will need more than passionate arguments and beautiful charts to convince them.”

“What will I need, Your Excellency?”

“Proof that you are worth the enormous risk you are asking us to take. Proof that you understand the dangers as well as the opportunities. Proof that you can be trusted with Spanish lives and Spanish gold.” Fonseca’s voice grew serious. “And proof that you are truly Spanish in your heart, not merely Portuguese in Spanish clothing.”

As Magellan left the bishop’s palace, his mind raced with possibilities and preparations. The audience with King Charles would be his greatest challenge yet — a teenage monarch who had never known failure, advised by men who had built their careers on caution and calculation. How could he convince them to risk everything on the word of a foreign defector?

The answer came to him as he walked through Seville’s narrow streets, past shops selling goods from across the Spanish Empire. He would not merely ask for Spanish support — he would offer to become Spanish himself, to merge his identity so completely with Spanish interests that his success would be Spain’s success, his failure Spain’s failure.

That night, he wrote a letter to his wife, trying to explain his choices and his hopes. “My dearest Beatriz,” he began, “I know you cannot understand why I have chosen this path, why I have left our homeland and our family to seek fortune in foreign lands. But I believe — I must believe — that this sacrifice will secure our son’s future in ways that remaining in Portugal never could. I am no longer the man you married, but I pray that the man I am becoming will be worthy of the love you have given me.”

As he sealed the letter, Magellan caught sight of himself in the room’s small mirror. The face that looked back at him was familiar yet strange — the same dark eyes and weathered features, but somehow transformed by determination and desperate hope. Fernão de Magalhães, the loyal Portuguese navigator, was truly dead. In his place stood Fernando de Magallanes, Spanish adventurer, ready to risk everything on an impossible dream.

The western route beckoned like a siren’s song, promising glory, wealth, and vindication. But first, he would have to convince a teenage king to gamble the future of his empire on the word of a man who had already abandoned one master for another. The greatest challenge of Magellan’s life lay ahead, and failure would mean not just the death of his dreams, but the destruction of everything he had sacrificed to achieve them.

Chapter 3: The Royal Gamble

Setting: Valladolid, Spain — 1517–1518

Magellan and Faleiro present their audacious plan to the teenage King Charles I (future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V). The young monarch, advised by seasoned counselors, must decide whether to risk enormous resources on the word of a Portuguese defector promising to deliver the riches of the East through an unproven western route.

The January wind howled across the plains of Castile as Fernando de Magallanes rode through the gates of Valladolid, his heart pounding with a mixture of anticipation and terror. Six months had passed since his first meeting with Bishop Fonseca, six months of careful preparation, political maneuvering, and the slow construction of a new identity. Now, on this bitter morning in 1518, he was about to face the ultimate test — an audience with Charles I, King of Spain and soon-to-be Holy Roman Emperor.

At eighteen, Charles was already one of the most powerful monarchs in Europe, inheriting not only the Spanish throne but vast territories in the Netherlands, Austria, and the New World. Yet he remained untested, a young man surrounded by experienced advisors who viewed every proposal through the lens of political calculation and financial risk. Convincing him to fund an expedition to find a western passage to the Spice Islands would require every ounce of Magellan’s skill, passion, and desperation.

The royal palace at Valladolid was a maze of cold stone corridors and political intrigue. As Magellan waited in an antechamber, he could hear the whispered conversations of courtiers and advisors, their words carrying hints of the debate that had been raging for weeks about his proposal. Some voices were supportive — merchants eager to break Portugal’s spice monopoly, young nobles hungry for adventure and glory. But others were skeptical, experienced diplomats who saw only danger in antagonizing Portugal and emptying the royal treasury on an untested foreigner’s dreams.

Beside him sat Rui Faleiro, now calling himself Ruy Falero, his transformation from Portuguese scholar to Spanish cosmographer nearly complete. The two men had spent countless hours refining their presentation, calculating routes and distances, preparing responses to every possible objection. Their charts were works of art — beautiful, detailed, and carefully crafted to emphasize opportunity while minimizing risk.

“Remember,” Falero whispered, “the king is young but not naive. He has been receiving conflicting advice from his council for months. Our success depends not just on the merit of our proposal, but on our ability to present it in a way that appeals to his ambitions while addressing his advisors’ concerns.”

Magellan nodded, but his mind was elsewhere, rehearsing the arguments he had been perfecting since leaving Portugal. This was his last chance — if Charles rejected his proposal, there would be nowhere else to turn. England was too weak, France too hostile to Spanish interests, and the other European powers lacked the resources for such an ambitious undertaking. Spain was his final gamble, and today would determine whether he would become the man who opened a new route to the Indies or simply another failed petitioner forgotten by history.

The great doors opened, and a herald announced their names with formal precision. “His Majesty will now receive Fernando de Magallanes and Ruy Falero, navigators and cosmographers in service to the Crown of Spain.”

The throne room was magnificent — soaring ceilings painted with scenes of Spanish victories, tapestries depicting the conquest of Granada and the discovery of America, golden columns that spoke of New World wealth. But Magellan’s attention was immediately drawn to the young man seated on the throne at the far end of the vast chamber.

Charles I was tall and pale, with the prominent Habsburg jaw that would become his defining physical characteristic. His dark clothing was elegant but austere, more suited to a scholar than a warrior-king. But his eyes — pale blue and unnaturally intense — held an intelligence and determination that belied his youth. This was not a boy playing at being king, but a monarch who had already begun to reshape the map of Europe.

Flanking the throne were the men who would ultimately decide Magellan’s fate. Bishop Fonseca stood to the king’s right, his expression carefully neutral. Beside him was Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, the aged regent whose conservative influence had shaped Spanish policy for decades. On the left stood Chancellor Jean Le Sauvage, a Fleming whose loyalty to Charles was absolute but whose caution in financial matters was legendary.

As Magellan and Falero approached the throne, their footsteps echoing in the vast space, Charles studied them with the same intensity he might apply to a military map or diplomatic treaty. When they reached the prescribed distance, they bowed deeply, and Magellan felt the weight of the moment settle on his shoulders like a lead cloak.

“Fernando de Magallanes,” the king said, his voice carrying surprising authority for one so young. “We have heard much about your proposal to reach the Spice Islands by sailing west. Our advisors are… divided in their opinions. Some see great opportunity, others great risk. We would hear from you directly — what exactly are you offering Spain, and what do you ask in return?”

Magellan had practiced this moment a thousand times, but standing before the Spanish throne, he felt his carefully prepared words scatter like leaves in the wind. This was no Portuguese king dismissing him with contempt, but a young monarch genuinely interested in his proposal. The opportunity was real, but so was the danger — one wrong word, one poorly chosen argument, and everything he had sacrificed would be for nothing.

“Your Majesty,” he began, his voice steady despite the hammering of his heart, “I offer Spain the key to the greatest commercial prize in the world — direct access to the Spice Islands, breaking Portugal’s monopoly and establishing Spanish dominance in the most profitable trade known to man.”

He gestured to Falero, who stepped forward with their charts. As the cosmographer unrolled the carefully prepared maps, Magellan continued his presentation.

“These islands — Ternate, Tidore, the Bandas — produce spices worth their weight in gold. A single ship’s cargo of nutmeg or cloves can purchase a palace, yet Portugal controls the only known route, forcing all of Europe to pay their inflated prices. But I have discovered a way to break that monopoly.”

Charles leaned forward slightly, his interest clearly piqued. “You speak of discovery, yet you have not yet sailed this route. How can you be certain it exists?”

“Your Majesty, I am certain because I have seen both ends of the passage. I have sailed the western coast of the New World with Spanish expeditions, and I have visited the Spice Islands themselves during my service with Portugal. The Americas must end somewhere in the south — they cannot extend indefinitely. When that passage is found, it will lead to an ocean that connects to the Indies.”

Cardinal Cisneros spoke for the first time, his aged voice carrying the weight of decades in Spanish service. “And what of the distance, Señor Magallanes? Even if such a passage exists, the western ocean may prove too vast to cross.”

Falero stepped forward, his scholar’s mind ready for the technical challenge. “Your Eminence, our calculations suggest that the western ocean is far smaller than commonly believed. The ancients greatly overestimated the size of the earth — our studies indicate that the distance from the American coast to the Indies is no more than three thousand leagues, easily manageable by a well-supplied fleet.”

The number was carefully chosen — large enough to seem credible, small enough to appear feasible. Neither man mentioned their private doubts about the true size of the Pacific, which their more pessimistic calculations suggested might be vast beyond imagination.

Chancellor Le Sauvage raised the question that Magellan had been dreading. “The financial requirements for such an expedition would be enormous. Five ships, supplies for two years, wages for two hundred men — we estimate the cost at nearly one hundred thousand ducats. Why should Spain invest such a sum on an unproven route proposed by a foreign navigator?”

The challenge was direct and devastating. One hundred thousand ducats — twice what Magellan had originally estimated, and a sum that could fund a small war. But he had prepared for this moment, studying Spanish finances and political priorities until he understood exactly how to frame his request.

“Your Excellency, one hundred thousand ducats is indeed a significant investment. But consider the return — if successful, this expedition would break Portugal’s monopoly on the spice trade, potentially generating millions in annual revenue for Spain. The Portuguese charge enormous prices for spices precisely because they control the only route. A Spanish route would not only provide Spain with direct access to these riches but would also drive down Portuguese prices as competition forces them to become more reasonable.”

He paused, letting the financial argument sink in before delivering his carefully prepared political appeal.

“Moreover, Your Majesty, this expedition would establish Spain as the premier maritime power in the world. Portugal built their empire by controlling the eastern route to the Indies. Spain conquered the Americas by daring to sail west when others feared to leave sight of land. This expedition combines both achievements — using Spanish courage and enterprise to reach Portuguese territories by a route that Portugal lacks the vision to attempt.”

Charles’s eyes lit up at the comparison to Columbus, and Magellan pressed his advantage.

“Your Majesty’s ancestors funded Christopher Columbus when every expert declared his voyage impossible. That single act of faith gave Spain dominion over half the world. Now I offer you the opportunity to complete Columbus’s original mission — to reach the true Indies by sailing west, to find the route to the Spice Islands that Columbus sought but never found.”

“And yet,” Bishop Fonseca interjected, his voice carefully neutral, “Columbus’s voyage, for all its ultimate success, did not achieve its original purpose. He sought the Indies and found America instead. What assurance can you give that your expedition will not suffer a similar fate — magnificent in its discoveries but failing in its stated goals?”

The question struck at the heart of Magellan’s proposal, and he knew his answer would determine the expedition’s fate.

“Your Excellency, Columbus sailed into the complete unknown, with no knowledge of what lay beyond the western horizon. I sail with the advantage of extensive knowledge of both the American coast and the Spice Islands themselves. I know where I am going and approximately how to get there. The only unknown is the southern passage around America, and even there, we have reports from Spanish expeditions suggesting that the continent narrows significantly in the south.”

He pulled out a particular chart, one that showed the southern tip of America as a relatively narrow strait rather than an impassable barrier.

“Moreover, Your Majesty, even if we fail to find the passage, the expedition would still provide valuable service to Spain. We would map the entire southern coast of America, potentially discovering new lands, new peoples, new sources of wealth. We would test the limits of Spanish seamanship and navigation, gaining experience that would benefit future expeditions. And we would demonstrate to the world that Spain is prepared to attempt what other nations dare not even imagine.”

Charles studied the charts with growing fascination, his young mind clearly captivated by the scope and audacity of the proposal. But when he looked up, his expression was troubled.

“There is another matter we must address, Señor Magallanes. You are Portuguese by birth, trained by Portuguese navigators, experienced in Portuguese territories. How can we be certain that your loyalty lies truly with Spain and not with your former master?”

The question hung in the air like an accusation, and Magellan felt the eyes of every advisor in the room fixed upon him. This was the moment of truth — would his transformation from Portuguese exile to Spanish patriot prove convincing, or would his foreign origins doom his proposal?

“Your Majesty,” he said quietly, “I understand your concern, and I do not take it lightly. Yes, I was born Portuguese, and yes, I served that crown for fifteen years. But I was cast out by King Manuel not for any failure of loyalty or competence, but because I dared to propose exactly what I am proposing to you now — a western route to the Spice Islands. Portugal rejected this opportunity because they are too conservative, too committed to their existing eastern route, too fearful of innovation and change.”

His voice grew stronger as he continued, passion replacing careful diplomacy.

“But Spain — Spain has never been afraid of innovation. Spain conquered the Americas when others said it was impossible. Spain defeated the Moors when others said it was hopeless. Spain is building an empire that spans the globe while other nations cling to their ancient territories and traditional ways. I offer my loyalty to Spain not because I have nowhere else to go, but because Spain is the only nation with the vision and courage to attempt what I propose.”

He stepped forward, as close to the throne as protocol would allow.

“Your Majesty, if I were truly a Portuguese spy, would I propose an expedition that would break Portugal’s most profitable monopoly? Would I offer to establish Spanish factories in territories that Portugal considers their exclusive domain? Would I risk everything — my life, my family’s future, my place in history — on a voyage that would make Spain Portugal’s greatest rival in the spice trade?”

Charles considered this logic, his pale eyes studying Magellan’s face for any sign of deception. Finally, he spoke.

“Your arguments have merit, Señor Magallanes. But loyalty is not merely a matter of opposing one’s former master — it is a question of commitment to one’s new one. What guarantees can you offer that your expedition will serve Spanish interests above all others?”

Magellan had prepared for this moment, crafting an offer that would bind his fate irrevocably to Spanish success.

“Your Majesty, I offer more than guarantees — I offer partnership. Make me a Spanish citizen, grant me Spanish titles, give me Spanish lands to call home. Let my success be Spain’s success, my failure Spain’s failure. I ask not merely to serve Spain, but to become Spanish in every sense that matters.”

The audacity of the request sent murmurs through the assembled courtiers, but Charles seemed intrigued rather than offended.

“You would renounce your Portuguese citizenship entirely? Accept Spanish nationality without reservation?”

“I have already renounced my Portuguese identity in everything but formal documents, Your Majesty. I speak Spanish, I think Spanish, I dream Spanish dreams of Spanish glory. All I ask is the opportunity to make that transformation official and complete.”

Cardinal Cisneros raised a practical concern. “And what of your family, Señor Magallanes? Your wife and child remain in Portugal. How can we trust a man whose heart remains divided between two nations?”

The question struck Magellan like a physical blow, reminding him of the personal cost of his choices. But he had anticipated this challenge as well.

“Your Eminence, my family will join me in Spain as soon as circumstances permit. My wife is a Portuguese noblewoman who married for love, not politics — she will adapt to Spanish life as I have adapted to Spanish service. My son will grow up Spanish, educated in Spanish schools, loyal to the Spanish crown. This expedition is not just about reaching the Spice Islands — it is about securing my family’s future in their new homeland.”

The king was silent for a long moment, consulting quietly with his advisors while Magellan and Falero waited in tense silence. Finally, Charles raised his hand for attention.

“Señor Magallanes, your proposal is both fascinating and terrifying. The potential rewards are enormous, but so are the risks. Before we can make a final decision, we must address several practical concerns.”

He gestured to Chancellor Le Sauvage, who stepped forward with a prepared list.

“First, the question of command. You ask for authority over five ships and two hundred men, many of whom will be Spanish nobles and experienced navigators. How can we ensure that foreign leadership will not create tensions within the expedition?”

Magellan had wrestled with this issue for months, knowing that Spanish pride would rebel against serving under a Portuguese commander.

“Your Majesty, I propose joint leadership with a Spanish captain-general who would share command responsibilities. I would serve as chief navigator and pilot, responsible for finding the route, while my Spanish counterpart would handle discipline, military decisions, and relations with Spanish crew members. This arrangement would combine my technical expertise with Spanish leadership and authority.”

“And if disagreements arise between you and this Spanish commander?”

“Then Your Majesty’s written instructions would resolve all disputes. We would sail under royal orders that clearly define our respective responsibilities and authorities.”

Le Sauvage consulted his notes again. “Second, the question of territorial claims. If you succeed in reaching the Spice Islands by this western route, how do we resolve potential conflicts with Portuguese claims to the same territories?”

This was the most dangerous question, touching on the heart of European politics and the delicate balance between Spain and Portugal. Magellan chose his words carefully.

“Your Excellency, we would be guided entirely by the Treaty of Tordesillas and our understanding of its geographical implications. If the Spice Islands lie on the Spanish side of the papal line when approached from the west, then Spain has every right to establish trading posts there. If they lie on the Portuguese side, then we would respect Portuguese sovereignty while still benefiting from the discovery of the western route.”

“And if the Portuguese resist Spanish presence regardless of treaty interpretations?”

“Then that resistance would demonstrate that Portugal has something to hide, that their claims to the Spice Islands may not be as legally sound as they pretend. Spain would be acting in good faith, attempting to determine the true geographical situation in accordance with papal authority.”

Bishop Fonseca raised the final crucial question. “What specific terms do you request if His Majesty approves this expedition?”

Magellan took a deep breath, knowing that his demands would either secure his future or destroy his chances entirely.

“Your Majesty, I ask for the following: First, appointment as Admiral of the Ocean Sea for any lands discovered during the voyage. Second, governorship of any islands or territories claimed for Spain, with these titles being hereditary for my family. Third, one-twentieth of all profits from the spice trade conducted via the western route. Fourth, the right to outfit one ship per year for trading voyages to the discovered territories. And fifth, Spanish citizenship and appropriate noble rank.”

The demands were staggering — titles, territories, percentages of profits that could make Magellan one of the wealthiest men in Europe. The courtiers buzzed with shock and indignation, but Charles seemed more amused than offended.

“You ask for much, Señor Magallanes. These terms would make you nearly a king in your own right.”

“Your Majesty, I ask for much because I offer much. If I succeed, Spain gains access to the most profitable trade in the world. If I fail, I lose everything — my life, my family’s future, my place in history. The reward should match the risk.”

Charles stood from his throne, a signal that the formal audience was ending. But his final words carried more hope than dismissal.

“Señor Magallanes, you have given us much to consider. We will consult with our advisors and provide you with our decision within the fortnight. In the meantime, we suggest you remain in Valladolid as our guest.”

As Magellan and Falero bowed and withdrew from the throne room, neither man dared to speak until they were safely outside the palace walls. Only then did Falero voice what they were both thinking.

“Fernando, I believe we have a chance. The king is interested — more than interested. But those terms you demanded…”

“Were necessary,” Magellan finished grimly. “If Charles approves this expedition with those terms, we will know that he truly believes in its potential. If he rejects them, we will know that he sees us as expendable adventurers rather than partners in a great enterprise.”

The next two weeks passed with agonizing slowness. Magellan walked the streets of Valladolid like a condemned man awaiting execution, analyzing every rumor, every glimpse of royal messengers, every change in the attitudes of courtiers who now treated him with nervous respect rather than dismissive courtesy.

Finally, on March 22, 1518, the summons came. Charles would see him again, this time in private audience with only his closest advisors present. As Magellan entered the smaller chamber, he found the king seated at a simple table rather than on his throne, the formality of their first meeting replaced by something approaching intimacy.

“Señor Magallanes,” Charles said without preamble, “we have decided to approve your expedition.”

The words hit Magellan like a thunderbolt, and for a moment he could not speak. After months of uncertainty, years of rejection, a lifetime of dreams deferred, success felt almost too enormous to comprehend.

“However,” the king continued, “we cannot accept all of your proposed terms. The governorship and admiralty you request would indeed be granted, but they will not be hereditary — they will be personal appointments that expire with your death. The percentage of profits will be one-twentieth as requested, but only for the first voyage. Future trading rights will be subject to renegotiation based on the success of this initial expedition.”

Magellan nodded eagerly. These were minor concessions compared to the magnitude of what he was being offered.

“Moreover,” Charles continued, “you will indeed receive Spanish citizenship and noble rank, but your command of the expedition will be joint rather than absolute. Juan de Cartagena will serve as your captain-general, representing Spanish interests and authority. You will be chief pilot and navigator, responsible for finding the route and conducting negotiations with native rulers.”

The appointment of a Spanish co-commander was not unexpected, but the choice of Cartagena was troubling. The man was a court favorite with limited sea experience — exactly the kind of political appointment that could doom an expedition. But Magellan was in no position to object.

“Finally,” the king said, producing an ornate document sealed with the royal seal, “here is your royal charter, formally authorizing the expedition and granting you the agreed-upon privileges. The Crown will provide five ships, supplies for two years, and wages for two hundred men. In return, we expect you to find the western passage to the Spice Islands and establish Spanish trading posts there.”

As Magellan accepted the charter with trembling hands, Charles leaned back in his chair with a slight smile.

“You should know, Señor Magallanes, that this decision was not unanimous among our advisors. Some believe we are throwing away a fortune on an impossible dream. Others worry that we are provoking unnecessary conflict with Portugal. But we are young, and we believe that young nations, like young men, must take bold risks to achieve greatness.”

“Your Majesty will not regret this decision,” Magellan said, his voice thick with emotion. “I stake my life, my honor, and my soul on the success of this enterprise.”

“See that you do,” Charles replied. “Spain is gambling its future on your western passage. If you succeed, you will be remembered as the man who broke Portugal’s monopoly and opened the Pacific to Spanish commerce. If you fail…”

He left the sentence unfinished, but the implication was clear. Failure would mean not just death for Magellan and his men, but disgrace for the young king who had bet so heavily on a Portuguese defector’s impossible dream.

As Magellan left the royal presence for the final time, clutching his charter like a talisman, he felt the full weight of what he had achieved and what he had committed himself to accomplish. The Portuguese exile had become a Spanish admiral, the rejected dreamer had become the leader of one of history’s most ambitious expeditions.

But success was still an ocean away, and that ocean was vaster and more dangerous than anyone yet imagined. The real test lay not in royal audiences or political negotiations, but in the unknown waters beyond the edge of every map, where Ferdinand Magellan would either find his passage to the Spice Islands or find his grave in the depths of an unnamed sea.

The gamble had been made, the die cast. Now came the reckoning.