The Enterprise of the Indies

In the fading light of the Alcázar of Córdoba, a worn Genoese mariner stakes his reputation, his soul, and a piece of mysterious driftwood against the skepticism of queens, archbishops, and royal cosmographers, demanding not charity but an empire in exchange for three ships and the audacity to sail west into oblivion. Christopher Columbus’s pitch to Ferdinand and Isabella explodes into a battle of theological fury, mercantile calculation, and geopolitical desperation as Spain’s newly victorious monarchs weigh whether this self-proclaimed prophet offers divine providence or a death sentence for Christian sailors chasing a madman’s miscalculations across an ocean that may swallow them whole.

The late afternoon sun filtered through the tall windows of the Alcázar of Córdoba, casting long shadows across the stone floor where Cristóbal Colón stood. He clutched his worn leather satchel, its corners frayed from years of traveling between courts, pleading his case to skeptical nobles and distracted monarchs. But today was different. Today, the sovereigns had finally granted him an audience in full court, with their most trusted advisors assembled to hear what he had come to call his Enterprise of the Indies.

Queen Isabella sat upon her throne with the regal bearing that had become her signature since uniting the kingdoms of Castile and Aragón with Ferdinand. Her auburn hair was drawn back beneath a jeweled headdress, her intelligent eyes fixed upon the Genoese mariner who had haunted her court for the better part of six years. Beside her, King Ferdinand leaned forward slightly, his fingers drumming against the armrest in a rhythm that betrayed impatience beneath his diplomatic composure.

To the queen’s right stood Hernando de Talavera, her confessor and now Archbishop of Granada. His face was stern, weathered by decades of devotion and scholarship. He had examined Columbus’s proposal before, had questioned its theological implications, its astronomical foundations. He remained unconvinced. Beside him, the Count of Tendilla, Íñigo López de Mendoza, watched with the practiced neutrality of a man who had survived the intricacies of court politics by keeping his opinions close until the opportune moment.

Luis de Santángel, the royal escribano de ración and a converso who had risen to considerable influence through his financial acumen, stood near the back. His presence was unusual for such a gathering, but his interest in the venture had grown steadily as Columbus made his case over the months. Where others saw theological problems or navigational impossibilities, Santángel saw potential returns on investment.

“Your Majesties,” Columbus began, his heavily accented Castilian carrying the weight of years of preparation. “I come before you not as a supplicant, but as a bearer of providence. God has placed upon my heart a vision that will bring glory to your crowns, wealth to your kingdoms, and souls to the Church.”

He stepped forward, emboldened by his own conviction, and spread before them a worn map marked with his own calculations and annotations. The parchment was covered with lines indicating trade routes, distances measured in leagues, and notes scribbled in margins during sleepless nights aboard ships or in borrowed rooms at monasteries.

“The world is round,” he declared, though this was not controversial among the learned men present. “And if it is round, then by sailing west, we must inevitably reach the East. The riches of Cathay, the spices of the Indies, the gold of Cipangu, all of these lie not beyond the Turk-controlled lands to the east, but across the Ocean Sea to the west.”

Archbishop Talavera shifted his weight, his disapproval evident in the set of his jaw. “We have heard these claims before, Señor Colón. The commission we assembled to review your proposal found your calculations—”

“Found them unconventional,” Columbus interrupted, a flash of defiance in his eyes. “But not impossible. Your learned men measured the Earth using Ptolemy’s estimates. I propose that Ptolemy underestimated the extent of the Asian continent, and that Marco Polo’s accounts suggest the riches of the Great Khan lie far closer to our shores than ancient geographers believed.”

He pointed to his map, his finger tracing the route he envisioned. “From the Canary Islands, I estimate no more than 2,400 nautical miles to the islands of the Indies. A journey of weeks, not months. Manageable with proper provisions and favorable winds.”

The Count of Tendilla leaned toward the king and murmured something. Ferdinand nodded, then spoke. “Your estimates differ markedly from those of our cosmographers, Señor Colón. They place Asia much farther to the west. The Ocean Sea between Spain and the Indies could be vastly larger than you suggest.”

“And if they are wrong?” Columbus countered. “The Portuguese sail south, year after year, seeking a route around Africa. How many ships have they lost? How many men? How much treasure spent pursuing a passage that may not exist, or may prove so treacherous as to be worthless for trade? I offer a direct route, a bold stroke that will place Your Majesties ahead of all competitors in the race for the riches of the East.”

Queen Isabella spoke for the first time, her voice measured and penetrating. “You speak of providence, Señor Colón. You speak of God’s will. Yet you come to us seeking titles, seeking wealth. You ask to be made Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Viceroy of any lands you discover, entitled to a tenth of all profits. These are not the requests of a humble servant of God, but of an ambitious man.”

The chamber fell silent. Columbus met the queen’s gaze without flinching. “Your Majesty, I do not disguise my ambition. But is it not the ambitious who achieve great things for their sovereigns? Ferdinand Magellan seeks glory. Vasco da Gama seeks glory. Should I be ashamed to seek the same while offering your kingdom an unparalleled opportunity?”

He drew himself up to his full height. “I ask for these titles not out of vanity, but because I must inspire crews to follow me across unknown waters. Men will not sail into uncertainty for wages alone. They must believe their captain possesses royal sanction, divine favor, and a stake in the success of the voyage. Give me these titles, and I will bring you an empire. Deny them, and this enterprise dies with my petition.”

Luis de Santángel stepped forward, breaking the protocol of his position. “If I may speak, Your Majesties?” Isabella gestured her permission. “The cost of this venture is modest compared to the potential returns. Three ships, provisions for perhaps a year, wages for ninety men. Against the costs of the Granada campaign or the maintenance of your armies, this is a trifling sum.”

Archbishop Talavera’s face darkened. “It is not merely a question of cost, Santángel. There are theological considerations. If Señor Colón is wrong, if the Ocean Sea proves far vaster than he believes, we send Christian souls to certain death. And for what? For gold? For spices? The Church cannot sanction such recklessness.”

“The Church,” Columbus said sharply, “sanctions crusades that send thousands to their deaths. The Church sanctions warfare against the Moors. Are sailors’ lives worth less than soldiers’ lives? And the souls I speak of are not only those of my crews. Consider the millions in the Indies who have never heard the Gospel. Is their salvation not worth the risk?”

The archbishop stiffened at this challenge to his authority, but before he could respond, the Count of Tendilla interjected. “The question of risk is legitimate. Señor Colón, you have sailed before. You understand the dangers of the open ocean. What makes you certain this voyage is even possible?”

Columbus pulled from his satchel a small piece of carved wood, weathered and strange. “This,” he said, holding it up, “washed ashore on Porto Santo, where I lived for years. It is carved by tools unknown in Europe or Africa. It came from the west, carried by the currents. And there are other signs. Portuguese sailors have reported strange plants floating in the waters west of the Azores. Birds that do not nest on known islands fly overhead at certain seasons, always heading west. The ocean is not empty, my lords. There is land beyond that horizon.”

Queen Isabella studied the carved wood, her expression unreadable. “You stake much on driftwood and birds, Señor Colón.”

“I stake everything on it, Your Majesty. My reputation, my life, my soul. I would not do so if I were not certain.”

Ferdinand leaned back in his throne, exchanging a long look with his wife. “Your certainty is admirable. But certainty is not evidence. Our cosmographers warn that your estimates of the Earth’s circumference are too small. If they are correct, and you are wrong, your ships will run out of supplies long before reaching any land.”

“Then let the cosmographers sail with me,” Columbus replied boldly. “Let them witness the truth with their own eyes. I do not ask Your Majesties to accept my word. I ask only for the means to prove it.”

Santángel spoke again, his merchant’s mind calculating. “Consider the moment we are in, Your Majesties. Granada has fallen. The Reconquista is complete. Spain stands poised to become a great power, but Portugal controls the African route, the Ottomans control the eastern trade, and the Italian city-states grow fat on their monopolies. This proposal offers a way to bypass all of them. If Colón succeeds, Spain becomes the gateway to the Indies. If he fails, we have lost three ships and a few thousand maravedís.”

“And what of the titles he demands?” Talavera interjected. “Admiral of the Ocean Sea? Viceroy and Governor? A tenth of all profits in perpetuity? These are extraordinary demands for an unproven venture. If he finds nothing but empty ocean, these titles become mockeries. If he finds riches, he becomes wealthier than most nobles in your court.”

Columbus turned to face the archbishop directly. “And what nobleman in this court has offered to sail into the unknown to bring glory to Spain? What duke or count has proposed to risk his life for the expansion of Christendom? I offer my skill, my experience, my life. In return, I ask for what any man of ambition would ask: recognition and reward commensurate with the risk.”

The Count of Tendilla smiled slightly. “He has a point, Talavera. We reward soldiers who conquer cities. Why not a mariner who proposes to conquer an ocean?”

Isabella raised her hand, silencing the growing debate. “Señor Colón, you speak with great passion and conviction. But passion has led many men to ruin. We have just concluded a ten-year war. Our treasury is depleted. Our people need rest. You ask us to embark on another great enterprise when we have barely recovered from the last.”

Columbus felt the moment slipping away. He had heard these words before, in Portugal, in Castile, in audiences granted and then withdrawn. But he pressed on, desperation lending force to his words. “Your Majesty, it is precisely because the war is over that this is the perfect time. Your soldiers have no more Moors to fight. Your ships sit idle. Channel that energy, that momentum, into exploration. Let the world see that Spain does not rest on past victories but reaches for new ones.”

He stepped closer to the throne, his voice dropping to an urgent whisper that nonetheless carried through the chamber. “Other nations are exploring. Portugal grows bolder every year. If you delay, if you hesitate, another monarch will seize this opportunity. King João of Portugal has already heard my proposal and rejected it. But what if he reconsiders? What if he sends his own expedition west while Spain deliberates? History will remember not the cautious, but the bold.”

Ferdinand spoke, his tone skeptical but intrigued. “You mentioned theological benefits. Souls for the Church. Elaborate on this. How do you propose to bring Christian salvation to lands you have never seen, inhabited by peoples you have never met?”

Columbus seized the opening. “The Great Khan, according to Marco Polo, expressed interest in Christianity. His letters to the Pope were never answered because the journey was too long, too dangerous. But if I can establish a direct route by sea, regular communication becomes possible. Missionaries can travel safely. Trade can flow both ways, not just goods but ideas, faith, civilization.”

He paused, letting the vision take shape in their minds. “Imagine, Your Majesties, Spanish priests celebrating Mass in the court of the Great Khan. Imagine Chinese converts traveling to Santiago de Compostela. Imagine the Church unified not just across Europe, but across the world. This is not merely about gold or spices. This is about the very expansion of Christendom itself.”

Archbishop Talavera looked troubled, his objections wavering in the face of this grand religious vision. The Count of Tendilla watched Columbus with new appreciation, recognizing a skilled rhetorician when he saw one. Santángel nodded slightly, approving of how Columbus had reframed the enterprise in terms the monarchs could not easily dismiss.

Isabella looked at her husband. A silent conversation passed between them, years of partnership and shared rule compressed into a glance. Ferdinand’s expression remained neutral, but he inclined his head ever so slightly.

The queen turned back to Columbus. “Your proposal requires consideration beyond what can be given in a single audience. We must consult with our advisors, review the costs, examine the implications. These are not decisions to be made hastily.”

Columbus felt his heart sink. He had heard similar words before, polite dismissals that led to months or years of waiting. But Isabella continued.

“However, we recognize the potential significance of what you propose. We will establish a formal commission to review your claims, examine your calculations, and provide us with a thorough assessment. You will make yourself available to answer their questions, to defend your positions, to demonstrate the soundness of your reasoning.”

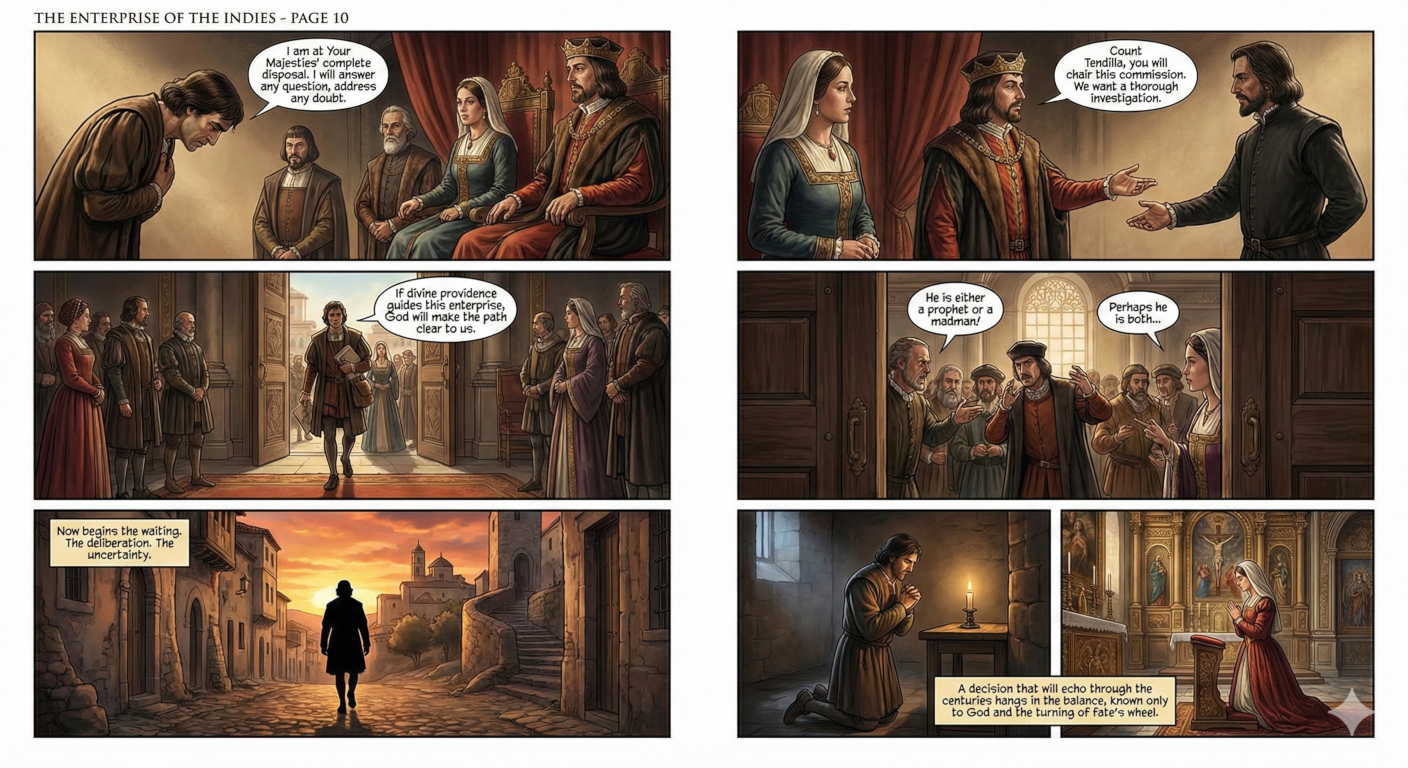

The mariner bowed deeply, recognizing this was as much as he could hope for today. “I am at Your Majesties’ complete disposal. I will answer any question, address any doubt, provide any evidence required.”

Ferdinand gestured to the Count of Tendilla. “You will chair this commission, Count. Select scholars, navigators, theologians, anyone whose expertise might illuminate the merits or flaws of this enterprise. We want a thorough investigation, not a superficial review.”

Tendilla bowed. “It shall be done, Your Majesty.”

As Columbus gathered his maps and prepared to withdraw, Isabella spoke once more. “Señor Colón, you claim divine providence guides this enterprise. If that is true, God will make the path clear to us. We will await His guidance, and the wisdom of our advisors, before rendering our decision.”

“May God grant Your Majesties wisdom,” Columbus replied, bowing again before backing out of the royal presence.

As the heavy doors closed behind him, the court remained silent for a long moment. Finally, Talavera spoke. “He is either a prophet or a madman, Your Majesty. I fear we are being asked to fund the latter.”

Isabella did not respond immediately. She gazed at the map Columbus had left on the table, its worn edges and careful annotations speaking of years of obsession. “Perhaps,” she said softly. “Or perhaps he is both. History suggests that prophets are often mistaken for madmen until they prove otherwise.”

“And if he is wrong?” Ferdinand asked. “If his calculations are as flawed as our cosmographers believe?”

Santángel interjected quietly. “If he is wrong, we lose three ships and some men. If he is right, we gain an empire. The mathematics of risk seem favorable, Your Majesty.”

The Count of Tendilla nodded. “And there is another consideration. Columbus will not wait forever. If we refuse him again, he will take his proposal elsewhere. To France, perhaps, or back to Portugal. Can we afford to let another nation discover a western route to the Indies while we stood by and did nothing?”

Isabella stood, signaling the end of the discussion for now. “We will see what the commission concludes. Until then, no more speculation. Let us deal with facts, evidence, and expert opinion, not dreams and ambitions.”

As the monarchs departed, their advisors lingered, already beginning the arguments that would dominate court discourse for months to come. Talavera gathered a group of like-minded skeptics, determined to demonstrate the impossibility of Columbus’s scheme. Santángel moved among the merchants and financiers, quietly building support for the venture among those who saw profit potential. Tendilla began the careful political work of assembling a commission that would be both credible and thorough.

Outside the Alcázar, Columbus walked slowly through the streets of Córdoba as evening descended. He had presented his case with all the passion and skill he possessed. He had invoked God, wealth, glory, and empire. He had challenged them, flattered them, warned them. Now it was out of his hands.

He found lodging at a monastery, as he so often did, living on the charity of monks who appreciated his religious fervor even if they doubted his geography. That night, unable to sleep, he sat by candlelight and wrote in his journal, recording every detail of the audience, every word spoken, every gesture observed. Someday, he told himself, these details would matter. Someday, people would want to know exactly how this great enterprise began.

But for now, all he could do was wait. Wait while learned men debated the size of the Earth, the extent of Asia, the feasibility of his calculations. Wait while courtiers whispered and plotted, building alliances for or against his proposal. Wait while Ferdinand and Isabella weighed the risks against the potential rewards, balancing the depletion of their treasury against the possibility of unprecedented wealth.

The commission would meet. Arguments would be made. Evidence would be examined. And eventually, in weeks or months or even years, a decision would be rendered. Either Spain would embrace this Enterprise of the Indies, or Columbus would once again find himself a rejected supplicant, forced to seek yet another patron for a dream that refused to die.

The candle burned low, casting flickering shadows on the monastery wall. Columbus closed his journal and knelt to pray, as he did every night, asking God to open the hearts of the monarchs, to reveal the truth of his vision, to grant him the opportunity to prove what he knew in his soul to be true.

Somewhere in the royal palace, Isabella too knelt in prayer, seeking divine guidance for a decision that could reshape the world. Beside her chamber, Ferdinand reviewed financial accounts, calculating costs and potential revenues with the practical mind of a king who had learned statecraft through war and diplomacy.

The stage was set. The arguments had been made. The players had taken their positions. Now, the great machinery of royal decision-making would grind forward, deliberate and inexorable, toward a conclusion that would echo through the centuries.

But that conclusion, that fateful decision that would alter the course of history, still lay hidden in the future, known only to God and the turning of fate’s wheel.